Roberto Sosa, a Honduran poet, wrote: “The poor are many: that is why it is impossible to forget them.” Yet somehow, daily, we manage to do the impossible.

Roberto Sosa, a Honduran poet, wrote: “The poor are many: that is why it is impossible to forget them.” Yet somehow, daily, we manage to do the impossible.

I am living in one of the poorest countries in the Western hemisphere where, according to the World Bank, one-third of the people live in extreme poverty, one-third in relative poverty, and only the final third are not poor (a cut off made at only $15 per day).

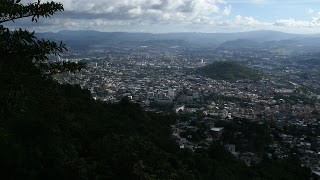

Despite two-thirds of Hondurans living in poverty, it is fully possible to spend a week or a month without interacting with them. The city where I live parts neatly into “two Tegucigalpas”—in which two-thirds of its residents ride public buses, buy their food in open markets, and buy their clothes used in the less-safe corners of the capital. The upper third, meanwhile, drive SUVs or sedans, buy their food in air-conditioned supermarkets, and go shopping for clothes and household goods in enormous, brightly-lit malls.

In the evenings, when two-thirds of the country have returned home, the upper third goes to theaters, museums, and galleries where they only see each other. The poor do not live in these neighborhoods. They do not go to their churches. They do not work in the offices of the rich, except perhaps as a sanitation worker or a security guard.

This is, of course, not a uniquely Honduran problem. Earlier this year, a resident of San Francisco (dubbed a “tech bro”) wrote an open letter to the mayor in which he articulated resentment for the way the worlds of the rich and the poor too often touch. He wrote that “the wealthy working people have earned their right to live in the city. … I shouldn’t have to see the pain, struggle, and despair of homeless people to and from my way to work every day.”

While rarely so callous as the ‘tech bro,’ few in the middle and upper classes in the States regularly share spaces with people who are poor. We live in an age of fast highways, comfortable vehicles, and air-conditioned malls where it is entirely possible to screen ourselves from images of destitution. In this splitting world, those who can avoid the ugly side of poverty generally do so. Not having to witness the needs of the marginalized can feel cleaner and more comfortable, less complicated and less guilty.

Poverty is uncomfortable. It is often ugly. It smells bad. It is unglamorous and desperate and challenging. The bus can be crowded and takes twice as long as a car. The open-air markets are chaotic, and they don’t sell peanut butter or oregano or the other familiar food. The man without shoes who badgers me on my way to church each Sunday holds his hand out and shouts, “Money!” which does not endear him to me.

I live in a community in Honduras where the third who are “not poor” would rarely find reason to enter. Water runs only twice each month. Sewers drain into the street and most people won’t walk outside after dark. This has allowed me to live alongside people in the middle third, those living in “relative poverty” – those who are getting by, but always on the edge. I live alongside these people, but not truly with them. On weekends, I go to parks or coffee shops, to the same museums and galleries of the rich. I am able to experience relative poverty only to the extent that I want to – after that, I buy the food I want to eat and go on my small vacations.

On the other hand, those living in extreme poverty—over 2.5 million—are invisible to me. They are the ones whose land is likely unregistered, whose identities might even go unregistered. They live tucked away in the hillsides eking out a living from cornfields and beans. They are sleeping on the streets in the city because there are no services for the homeless or mentally ill. They are children selling peanuts to cars at intersections or juggling wads of cloth lit on fire. Occasionally when I venture downtown I will notice their hands held out, but other times they blend into the background, which I don’t even see.

Most of the two-thirds don’t vote. They don’t write petitions. They don’t run for office or go on the news. Even though they outnumber those with means, even though they are many, they are not heard. The chasm that divides the poor from rich runs deep and wide. It takes concerted effort to cross this divide. It is easy to willfully forget – privileging the comfort of the few over the rights of the many to be seen, to be engaged, to be acknowledged as neighbors. But we must not allow ourselves to forget.

“The Poor”

by Roberto Sosa

(translated from Spanish by Spencer Reece)

The poor are many

and so—

impossible to forget.

No doubt,

as day breaks,

they see the buildings

where they wish

they could live with their children.

They

can steady the coffin

of a constellation on their shoulders.

They can wreck

the air like furious birds,

blocking out the sun.

But not knowing these gifts,

they enter and exit through mirrors of blood,

walking and dying slowly.

And so,

one cannot forget them.

https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine/poems/detail/55411

Katerina Parsons served with Mennonite Central Committee’s Service and Learning Together (Salt) program from 2015-2016 in Tegucigalpa, Honduras, where she worked as a communications associate at the Association for a More Just Society (AJS). AJS is a Christian organization dedicated to making government systems work for the poor and vulnerable in Honduras, particularly in cases of violence and corruption. Upon completion of her SALT term, she continued on with AJS in Tegucigalpa, this time as Director of US Communications.

This post is part of our “Anabaptist Young Adults in Mission” blog series. To view all posts in the series, please click here.

Comments on this Blog entry

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.