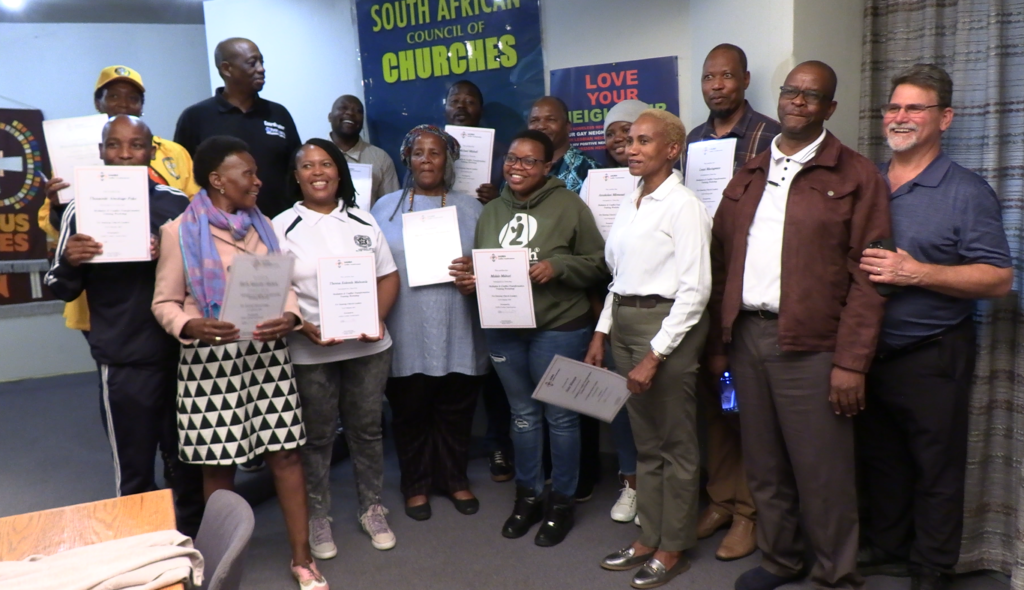

Front: Rev. Shiela Hlobelo, Mama Eulanda Mabusela, Mama Phinah Phokanoka, Rev.Nicky Motsepe, Steve Wiebe-Johnson.

Front: Rev. Shiela Hlobelo, Mama Eulanda Mabusela, Mama Phinah Phokanoka, Rev.Nicky Motsepe, Steve Wiebe-Johnson.

Back: Toto Nzamo, Moora Letsoalo, Amukelani Mkwanazi, Pastor Lwazi Macingwane, Oscar Siwali, Mulalo Mahori, Pastor Gosiame, and Bishop Mtshali.

Mennonite Mission Network — The four-hour power outage that occurred just seconds before the conflict mediator training session began added irony that illuminated the group’s purpose and resolve.

The rain and darkened clouds would not dim the light they all knew they must bring to solve dire social problems in their communities.

“The Bible speaks about caring for the poor and the vulnerable,” said Oscar Siwali, founder and director of Southern African Development and Reconstruction Agency (SADRA), as he scanned the group of church leaders sitting closely in a circle near the window. “We cannot be quiet at such a time as this.”

The conflict mediator training was held at the offices of the South African Council of Churches in Johannesburg, South Africa, the organization that was once headed by Bishop Desmond Tutu. Siwali had flown two hours from his home in Cape Town, South Africa, in the early morning to lead the final session for these church leaders to become certified conflict resolution mediators. SADRA Conflict Transformation, a Mennonite Mission Network partner, offers a three-day certified peace education and training program for church and community leaders across the country, including participants from all denominations. It also offers a four-day version of the training for youth in schools.

SADRA has trained more than 2,200 mediators throughout South Africa since its launch in August 2013, with the majority being Christians. A 2010 study by The Pew Charitable Trust shows that 74% of South Africans respect and trust religious leaders and identify religion as important in shaping their daily decision making. Citing these statistics, Siwali, a former pastor, explained that training religious leaders as skilled mediators can reap particularly powerful community benefits.

Siwali invited the Johannesburg trainees to share how they were applying the skills they had learned in SADRA training sessions. The trainees talked about situations they had encountered, such as sexual violence in homes, bullying in schools and conflicts between churches. These problems are certainly prominent in other industrialized nations, such as the United States, but they are particularly acute in South Africa, because apartheid’s atrocities remain deeply imbedded in current life. During his 2023 state of the nation address, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa emphasized fighting sexual violence as a priority of his administration.

Despite South Africa’s breathtaking beauty and increased prosperity since apartheid ended, the country’s fragile social order, political climate and infrastructure is equally apparent. For example, the rolling blackouts called “load shedding” that caused this meeting to be held in near darkness are, in part, the result of a grid that was built generations ago to service only South Africa’s 8% White minority now buckling, as it tries to supply the needs of the entire nation. These challenges, ironically, also provide an opportunity for the church to bring hope — to be the light of the nation.

Siwali and the trainees pondered whether the church was having enough of a positive impact on South Africa’s society, particularly in the Black communities that have been deprived for far too long.

Pastor Gosiame Choabi of Johannesburg urged against generalizing church leadership and acting as though all leaders think and behave the same.

“We tend to take for granted that all church leaders are informed,” he said. “We tend to take for granted that all church leaders are activists. We need to identify the critical leaders who are in the know and work together.”

Siwali expressed that the church has been too quiet in addressing social problems. Referring to the biblical theme in Esther 4, Siwali said Black church leaders need to take risks and seek community support to relieve suffering. He urged that, in becoming certified conflict resolution mediators, they were extending SADRA’s mission to equip and revive the church — to “take the pulpit back into the community.”

This is why Siwali invests in equipping like-minded leaders with systematic, sound mediation training. One example of this type of activism is being done by Eulenda Mabusela and Phinah Phokanoka at Filadelfia Secondary School in Soshanguve (Gauteng Province) — a school they describe as having a reputation of “shame.” There has been tremendous animosity among students, teachers and parents.

“We had several sessions with teachers in which we made them aware of how important they are …” Mabuesela said. “We dedicate every Monday to prayers sessions, because we believe God will open doors.”

Established in 2013, SADRA is a registered South African non-governmental organization, based in Somerset West, a town in the country’s Western Cape Province. SADRA helps foster tolerance and non-violence, using conflict transformation methods, such as dialogue and mediation, to resolve differences. For the past 10 years, SADRA has provided conflict management training to local government officials, community leaders and youth. SADRA peer mediators address issues such as bullying and gangs in schools. SADRA mediators confront intense topics, such as land disputes and union conflicts. SADRA anticipates a major role in the upcoming national elections, which may become volatile.

Siwali gave feedback and suggestions about how their mediation training could be applied in various areas of the community, such as in family courts and divorce courts. Siwali said SADRA received a contract with the court in Cape Town to help with mediation for spouses. One abusive husband accepted Siwali’s invitation to become a disciple of Jesus Christ. He stopped being abusive, and the couple remained married.

As Siwali spoke, suddenly the light returned to the meeting room.

The load-shedding blackout had ended.

Siwali transitioned to leading the group in their certificate ceremony. Each graduate handed a certificate to another graduate and spoke words of encouragement and affirmation.

Comments on this Blog entry

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.

I would like to see some statements confirmed by data. Are problems like sexual abuse indeed “particularly acute in South Africa, because apartheid’s atrocities remain deeply imbedded in current life”? This could be confirmed or refuted by comparisons with other African countries.

And some criticism sounds childish, e.g. of course the electrical grid did not start servicing 100 percent of the population. It started, like everywhere, in a small way. What would be interesting is: In what way has it been broadened over the years? A graph would be very helpful here.

It seems that the churches are willing to solve or transform small conflicts (family, school etc.), but are rather shy to address the big racial and political conflicts!