Mennonite Brethren Beginnings in the Chocó

The early history of the Mennonite Brethren churches in the Chocó region of Colombia reveals a church struggling to adapt and live the gospel in a context marked by systemic poverty and isolation, thick relational networks, and a strong communal orientation.1 Bound by the western cordillera of the Andes to the east and the Pacific Ocean to the west, the Chocó’s geographic isolation has been compounded by centuries of neglect, first by colonial Spain and then by the independent Republic of Colombia. Today the region has the highest rates of poverty in the entire country2 and, increasingly, some of the highest rates of violence, due to the presence of illegal armed groups. Throughout their history, the Mennonite Brethren in Chocó have also faced additional challenges as a church body, first as a marginalized and oppressed religious minority during Colombia’s decade-long civil war known as La Violencia and then when their denomination restructured in the 1960s, leaving the Chocó churches with significantly fewer resources and institutional support.

As Chocoano3 Mennonite Brethren accepted the gospel and applied it to their particular context, they began to do their own theological work, eventually departing from interpretations privileged and taught by the missionaries. In this process, they used the material of their everyday life—most significantly food—to explain what Christian conversion and practice meant for them. Food became a resource for their self-theologizing and maturation as a faith community, allowing them to profess and maintain a nondualistic theology that informed and honored the experience of their daily lives, despite widespread theological polarization in Latin America during the 1960s and 1970s.

Far removed from Colombia’s central highlands, the young Russian-Canadian Mennonite Brethren who arrived in the lower San Juan region in 1947 were at first seen as a curiosity. The region was predominantly Afro-Colombian and indigenous, with few Colombian mestizos and even fewer foreigners. As white English-speakers, the Mennonite Brethren missionaries were a novelty in the region. Despite the interest their presence generated, initially there were few indigenous people whose curiosity led them to join the missionaries’ faith. The general reluctance the missionaries encountered was due to numerous contextual factors: a historical lack of equitable relationships between blacks and whites, dissonance between a matrifocal Chocoano society and a patriarchal missionary culture, and rising anti-Protestant sentiment in the 1950s.4

During the colonial period, the Spanish sent African slaves to the Chocó to extract the region’s vast gold deposits. Unlike other Spanish mining operations in Nueva Granada, the owners of the Chocó mines did not live on site, choosing to manage the rudimentary mining operations from afar.5 Mining profits were immediately extracted from the Chocó, resulting in “small and ill equipped” mining towns in the Chocó itself.6 Because the Chocó was considered a frontier territory, settlement patterns were very different than in other regions; there were few Spanish settlers and no large urban centers in the Chocó during the colonial period.7 This arrangement led to a population that was heavily African-descendent and indigenous, unlike other regions where there was much more intermixing with the Spanish.8 During the colonial period, slaves and free blacks maintained a system of alternative economic activities that constituted a significant form of resistance to the slave system.9 After emancipation these economic patterns continued; even into the 20th century blacks in Chocó preferred to spend their time working in subsistence agriculture and mining, rather than working for whites.10

The Catholic Church did not really establish a presence among Afro communities in the Chocó until 1878 when the Capuchins arrived.11 Catholicism was slowly accepted thereafter, and many African elements were woven into popular faith expressions.12 The first Protestants to start formal mission work in the Chocó were the Gospel Missionary Union (GMU), who began in the department capital of Quibdó in the early 1940s. In the San Juan region south of Quibdó, however, there were no formal Protestant missions or churches before the arrival of the Mennonite Brethren in 1947, although colporteurs—peddlers who sold Bibles, Bible portions, and evangelical tracts—had passed through the region on occasion. Since the GMU was already working in Quibdó and nearby villages, the Mennonite Brethren looked further south to the San Juan River basin, eventually settling in Istmina. Although Istmina itself was a town of less than 3,000 people, there were around 19,000 people living in the rural regions and villages within the municipality, a fact that would drive extensive evangelism efforts along the region’s more remote tributaries.13

The Chocó is crisscrossed by a web of rivers that are the center and sustenance of daily life there. Before slavery was abolished, runaway slaves established and lived in dispersed communities along river tributaries deep in the forest.14 Even in the 20th century, most subsistence occupations took place in the river, or at least alongside it. Nearly all transportation—with the exception of foot travel—also happened by river. For many, the river was the primary cultural and social focus.15 Given the general lack of roads in the region, Istmina’s strategic location at the confluences of the San Juan and San Pedro Rivers guaranteed the Mennonite Brethren access to communities downriver all the way to the Pacific Ocean.16 By the 1950s the Mennonite Brethren and their ministries were known up and down the San Juan River and its tributaries, even beyond what could be traveled in a multiple-day canoe trip.

La Violencia: Mennonite Brethren Faith in the Context of Civil War

Despite a widespread appreciation for the missionaries and their work, the first decade of Mennonite Brethren presence resulted in few conversions.17 Instead, the earliest years of Mennonite Brethren history in Colombia overlapped with a ten-year civil war known as La Violencia (1948–58). Traditionally understood as a conflict between Liberals and Conservatives, La Violencia was notable for the high degrees of brutal violence that erupted in the Colombian countryside. Protestants, however, are most likely to remember La Violencia as a period of religious persecution. Catholicism had been the predominant religion in Colombia since the colonial period and, during La Violencia, was relied on to unify Colombians across political lines. The flip side was that Protestants were marginalized and discriminated against to a heightened degree during the same period.

Although the Chocó was mercifully spared much of the physical violence associated with La Violencia, Mennonite Brethren believers and missionaries dealt with interruptions of their services, school closures, mild stonings, harassment, and anti-Protestant processions. Such opposition led to small, slow-growing communities. The Mennonite Brethren mission newsletter regularly reported on individuals who, although sympathetic to the gospel, struggled to make a final decision because they were afraid of the priest and their neighbors.18 Those who did make a public decision of faith often faced ridicule and ostracism. In 1950, for example, hundreds of people turned out to mock the five believers from Istmina who entered the waters of the San Juan for baptism.19

These experiences were shared by Protestants across Colombia, but in 1953—five years into La Violencia—the government designated the Chocó as a “mission territory” through a formal agreement with the Vatican. The Treaty of Missions designated the most unpopulated regions of the country—geographically large but representing a small percentage of the population—as Mission Territories under the direction and control of the Catholic Church.20 In addition to the opposition and social marginalization that accompanied conversion, the Treaty of Missions forced Chocoano believers to negotiate an array of ever-changing legal restrictions. Through a series of circulars released between 1953 and 1955, the Treaty of Missions evolved to ban Protestant education, outlaw Protestant meetings in homes and church buildings, and forbid foreign missionaries from meeting with Colombians.21 Mennonite Brethren believers and missionaries in the Chocó navigated this constantly changing legal landscape by frequently adjusting their worship times and practices, their meeting places, and their degree of involvement in the community at large. These years functioned as a crucible for the Mennonite Brethren church in the Chocó, refining and focusing the core of their ecclesiology and expanding Chocoano leadership within the church.

The most difficult year was arguably 1956, when religious meetings of all kinds were not just restricted but outright banned. In April of that year, all evangelism activities were suspended, the chapels closed, and foreign missionaries prohibited from meeting with Colombians. Activities in all areas were affected: Mennonite Brethren were forced to stop preaching in Condoto, prohibited from continuing with the building of a new chapel in Istmina, and threatened at knife point to stop building plans for chapels in nearby rural communities.22

Despite the new restrictions, Mennonite Brethren in the Chocó refused to comply with government mandates. Even though meetings were prohibited, believers continued to gather for worship and study, albeit behind closed doors. Instead of gathering in the church chapel with missionaries present, Chocoano believers hosted and led meetings in their own homes. Since homes were the domain of women, this situation increased female leadership and participation as well; during this period, women who hosted home groups for worship were known to lead group discussion based on the scripture.23 In Istmina, believers met in each other’s homes for Sunday morning worship, in four or five different locations all over the town.24 A few months later, a missionary reported that “the national Christians were encouraged to meet in their own homes and soon very interesting reports came in.”25 Occasionally the total combined attendance in the home meetings topped the former attendance in the chapel, suggesting that intimate worship spaces with Colombian leadership—and more female leadership—were more attractive to Chocoanos than the public missionary-led services.26

“Hungry for the Word”: Home-Based Services and Chocoano Theologizing

It is in the context of home meetings that we see some of the first examples of Chocoano theologizing emerge; the opposition that believers faced forced them to identify and claim the beliefs and practices that were most central to their faith, allowing more peripheral ones to fall by the wayside. When asked to account for their faith before local authorities, believers used food as a resource to articulate their emerging ecclesiology as a community. One Sunday morning in 1956, two policemen interrupted a worship service at a home in the neighborhood of Pueblo Nuevo in Istmina and ordered everyone to leave. In response, a believer stepped forward and told the policemen that the group had gathered “not because they were invited with church bells like in the Catholic church but because they were hungry for the Word,” and that they would not be intimidated. Next the policemen questioned Francisco Mosquera, who was on the church council at that time. They asked him if he ever had services in his home, and Mosquera answered, “Yes, every day.” When further questioned on how many such services he had hosted, he said, “My family is evangelical, and just as I don’t know how many times I eat, I don’t know how many times I have conducted a service in my home. We have them every day.” The policemen then left but only after threatening to shoot should they encounter the group gathered a second time. Despite these threats, the group continued to meet regularly in direct resistance to the persecution enacted against them.27

The testimony of Francisco Mosquera and other believers in Pueblo Nuevo gives us an insight into an ecclesiology that was being forged amid difficult circumstances. They gathered not because they were compelled by outside forces—in fact, much of their environment was designed to prevent their gathering—but because they desired, even needed, to do so. Mosquera likened their worship to eating, a daily practice necessary for survival, while the other believer described the impetus as a “hunger.” Amid persecution, Mennonite Brethren in the Chocó came to see the gathering of believers and the sharing of the Word being as necessary for their survival as the fish and plantain they ate daily. Secondly, their hunger and need was defended and practiced in a communal context, just as daily meals were eaten and shared within the family. Believers “ate” the Word together, gathered in homes sometimes filled to bursting. The communal aspect of their practice was significant, especially given the context of persecution in which individual Bible study would have drawn relatively little attention. Finally, their willingness to meet and satisfy their hunger in a variety of locations, including riversides and members’ homes, decoupled worship from any particular place and reaffirmed an understanding of the church as the gathered community.

Leading up to 1957, the presence of resident missionaries in the region prevented much indigenous theologizing. Because of the legal restrictions enacted by the Treaty of Missions and the leadership roles assumed by Chocoano believers in this period, however, the home meetings provided a unique environment for theologizing apart from missionary input. In fact, the testimony of the believers in Pueblo Nuevo is one of the first examples we have of Chocoanos theologizing, defining the contours of their faith in their own language. Significantly, the language they chose to use to describe the faith before local authorities was the language of food and daily sustenance, something all people would be able to relate to. Following the most intense period of persecution, Francisco Mosquera became the first Chocoano pastor of the Istmina church. His role as a house church leader and his experience in defying official mandate to maintain—and thus define—the community’s faith practices led to a new era of Chocoano leadership and indigenous theologizing within the Mennonite Brethren church in the Chocó.

Shifts in Mennonite Brethren Mission Strategy

As La Violencia drew to a close toward the end of the 1950s, religious opposition to Mennonite Brethren in the Chocó rapidly declined, and believers in the Chocó welcomed their new religious and civic freedoms with open arms. Just as the political environment became more stable, however, changes in the structure of the Mennonite Brethren mission brought new challenges that impelled believers to more fully develop the theological conclusions they had drawn during La Violencia. For the first eleven years of Mennonite Brethren history in the Chocó, the mission’s institutions and outreaches defined Mennonite Brethren identity and activities in the region: medical dispensaries in Noanamá and Istmina, traveling medical services in the countryside, lumber mill, mechanics shop, employment opportunities in the mine in Andagoya, and alternative educational options for Mennonite Brethren children.

Many of the mission’s projects were also intentionally designed to generate jobs for evangelicals in the Chocó, and many early converts received jobs through the mission. As a young man, Mennonite Brethren elder Dagoberto Minota worked in the mechanics shop. In his words, “My career comes precisely from the gospel.”28 Minota’s wife, Ruffa Gutiérrez, started her nursing career by working at the mission’s dispensary. Missionary John Dyck was particularly interested in improving the economic situation of the people in the churches and was renowned for either directly employing believers at mission institutions or finding work for them at the Chocó Pacific Mining Company.29 Many of those living in the rural regions surrounding Istmina, which was historically a mining region, were still involved in subsistence mining in the mid-twentieth century. By the time the Mennonite Brethren arrived in the late 1940s, however, international mining companies had been in the region for over thirty years. Dominating the economic landscape, the Chocó Pacific Mining Company extracted and exported resources from the Chocó at an incredible rate. There were few accompanying investments, however, and the region surrounding Istmina remained economically disadvantaged and underdeveloped, despite decades of gold and platinum extraction worth millions.30 In the 1940s and 1950s, however, the mine was one of the largest providers of steady employment in the region. “[John Dyck] had a very good relationship with them [the miners] and so, for many here—I remember around six people that were believers—he influenced the mine so that they would give them [the believers] work,” recalled Victor Mosquera, a church member in Istmina. “So they were given jobs, and they worked there until they retired.”31

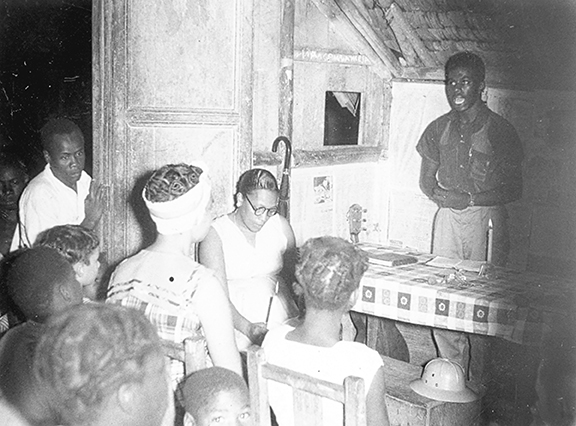

Among the many institutions founded by the mission in these early years, the most significant was arguably the medical dispensary in Istmina. Established in 1947, the dispensary provided an alternative option for quality health care at a low cost and improved the reputation of Protestantism in that region. Since the mission subsidized the cost of drugs and paid the living expenses of the missionary nurses, a consultation at the dispensary was available for a minimal fee of ten centavos.32 And although the dispensary benefited the evangelicals in Istmina, especially, many more non-evangelicals sought health care there. During four months in 1955, for example, the dispensary saw 737 patients from a total of fifteen different villages; in 1960 it served 8,926 patients.33

Although the dispensary was closed by the government multiple times during La Violencia, the missionaries made it a priority to reopen the clinic whenever possible. Through a variety of adaptations, single female missionaries and Colombian women worked to provide consistent health care to residents in and around Istmina, despite restrictive legislation and frequent government closures. Missionaries sought to fulfill ambiguous federal requirements, while local women working as nurse aids oversaw daily operations and treatment. In the most dramatic examples, these women—missionary and Colombian alike—maintained a schedule of secret, underground home visits that were intended to preempt another government shutdown. The dispensary was widely perceived as a service of the church, and the energy those women dedicated to keeping the dispensaries running testified to a faith that was not based just on words but also on action in the community at large. Indeed, the dispensary is one of the most revered and frequently cited ministries of the church by elderly Chocoanos with memory of that period.34 Hernán Mosquera described the dispensary in the following way: “In Istmina there was a dispensary or pharmacy. And the people needed medications . . . but the goal was to enact the gospel.”35 Mosquera’s comment makes clear that believers understood the dispensary to be a legitimate and central expression of the gospel and the church’s practice of it, something worth maintaining, even in times of opposition.

Many older evangelicals in Istmina look back on this period as the church’s “golden” period, when part of the church’s mission was to work for the economic betterment of its people. Yet there were drawbacks to linking so many heavily funded institutions and projects to the nascent churches. These institutions had the tendency to join conversion with economic gain, they mimicked a mission station model that imposed an all-encompassing foreign structure on a local system, and they were completely unsustainable from a financial perspective; there was no way the small churches in the Chocó could provide the finances needed to maintain the institutions. Ultimately, they were institutions created by foreign outsiders, not believer-driven projects that were conceived and designed by the communities themselves.36 Over time these weaknesses became apparent. The mission slowly came to realize that it would not be able “hand over” the institutions that it had built, due to the high financial investment required to maintain them.

Partially as a result of these challenges, the mission decided to overhaul their organizational and administrative structure, shifting the center of Mennonite Brethren mission and denominational administrative activity from Chocó to Cali, the capital of neighboring Valle del Cauca. Growth in the Chocó had been minimal—there were only thirty-two members in Mennonite Brethren churches in the Chocó in 1957—while Cali was growing at an incredibly rapid pace.37 In order to take advantage of Cali’s rapid urbanization and encourage the growth of national leadership and a more sustainable church structure in the Chocó, beginning in 1957 the mission decided to scale back investments in the Chocó and centralize efforts in Cali. Over the next few years, the mission institutions—including the medical dispensary—closed, all resident missionaries left, and attendance declined in the churches in Chocó. These changes were preceded by an almost complete turnover in missionary personnel between 1955 and 1957, including the sudden and tragic death of missionaries John and Mary Dyck in a plane crash, leading to very little consistency in the mission’s approach to its relationships with the churches in Chocó and a general lack of firsthand experience of the Chocó and its context among the Mennonite Brethren missionaries.38 Meanwhile, new evangelical groups moved into the region, more and more Chocoanos were choosing to live in town centers, and the big mining companies shut down. The changes within both the San Juan region and the Mennonite Brethren mission had a significant impact on the churches in the Chocó—they went from being the only evangelical denomination in the region to being one of many, from being the center of the Mennonite Brethren to being on the periphery, from having personal relationships with mission institutions and resident missionaries to institution-mediated relationships.

Theological Polarization and the Mennonite Brethren Churches in Chocó

These new circumstances profoundly challenged the theology and practice of the Mennonite Brethren churches. They still had a “hunger for the Word,” but their faith was now unmoored from a mission structure that provided believers with employment and other material benefits that could help assuage their physical hunger as well. In this uncertain period, Chocoano Mennonite Brethren began to articulate a holistic theology that defied the theological polarization of the 1960s and 1970s. Just as it had served as a sustaining metaphor during the years of religious oppression, Chocoanos now turned to food as a source for articulating a holistic theology that reflected their understanding of the gospel and of their faith in Jesus Christ in light of their own context.

The close link between the churches and the mission’s socioeconomic initiatives before 1957 led to a particular understanding of Mennonite Brethren faith in the region. Gabriel Mosquera remembers how the mission’s approach, primarily directed by John Dyck, was perceived in those years:

[John Dyck] had an unusual vision. He said, “Wherever the gospel is, there should also be a school, a workshop, a medical center, and at least [some] agriculture.” So this vision was revolutionary. Of course! It was surprising. The people had never seen someone, even the government, arrive with a similar idea in their head. So he came to Istmina to start a school. That was his dream, and he did it. And he had a mechanics shop and said, “The young people are going to learn mechanics or nursing, something that serves the Chocó.” Then John Dyck died, and it was a hard blow for the Chocoanos, even for non-believers. Look what he did. In this period there were no cement foundations [for buildings—everything was wood or dirt], and he constructed a number of these. He created transportation, health [services], a different vision.39

Despite some of the critiques of the early mission structure, the believers in Chocó reclaimed the dispensary, mechanics shop, and other projects as evidence that the gospel had something to say about earthly poverty and physical well-being. From their interactions with these institutions and projects, Chocoano believers had drawn theological conclusions about what it meant to be Mennonite Brethren in the Chocó. Precisely because of institutions like the medical dispensaries and schools, material matters of health, education, food, shelter, and occupation had become intimately connected to the presentation and reception of the gospel. To believers in the Chocó these institutions demonstrated that physical and material well-being mattered and were part and parcel of the gospel. This conviction was strengthened during the persecution years, when ministries like the dispensary were maintained despite great personal and financial cost. Just as it was worth resisting the religious opposition they had faced during La Violencia, many concluded, so also was it worth resisting the forces of poverty and inequality in their communities.

During the transition period toward centralization in Cali, however, the mission began to define such theological conclusions as dangerous to the success of the church. Gabriel Mosquera remembers:

After [John Dyck’s death] a very intelligent young missionary arrived, [with] a much more conservative North American vision. He didn’t agree with what John Dyck had done, so things began to change. He only focused on evangelism and the gospel, nothing else mattered.40

Yet many Chocoanos had originally been attracted to the gospel precisely because they perceived it had something to do with the needs of their context, with the matter of daily bread. The conflict between these two approaches produced a theological crisis for many within the church. The missionary who replaced Dyck was Alvin Voth, who moved to the Chocó as a resident missionary with his wife in 1961. Voth was tasked with streamlining the mission’s role in the Chocó. In documents, Alvin Voth revealed that one of their main goals and struggles was to “correct” the connection between evangelical faith and economic benefits that had developed in the region.

We will have to say no, to those who come with outstretched hand and say, “Give me, lend me, help me. I want to join your faith, but help me feed my family, educate my child in your schools, give me a job, give me free drugs for my sick wife and child:” . . . Almost every week we offend believers and church members, because we have to say no and point them to the Lord instead.41

Voth perceived that an unhealthy economic dependence had developed between foreign missionaries and Colombian believers, and he saw the roots of this dependence to be spiritual. In a presentation before the Missionary Fellowship in 1963, Voth compared the Chocó churches to the believers on the road to Emmaus. Just as those on the road to Emmaus expected Jesus to redeem Israel, said Voth, so the Chocoanos expected their faith to redeem the Chocó.

The great expectation in the Chocó is for a national and social Christ and a Gospel to match. Few have been the disciples who have looked beyond this life level and really grasped the spiritual implications. . . . We cannot meet the social needs of the area. That is impossible. We cannot expect to establish a church that will meet all the needs of a people needy in every area of life. If social services displace, even in the smallest measure, the basic ministry of preaching and teaching the Word of God, a weak and materially dependent church will develop.42

In order to reconcile the reality of great need with the changing mission policy, missionaries like Voth began to argue that true Christian faith was primarily spiritual and divorced from the material needs of earthly life. From the mission’s perspective, the integration of spiritual and material distracted the church from its true purpose.

This was not a perspective unique to the Mennonite Brethren missionaries. Rather, it echoed a rising religious polarization in Latin American in the context of the Cold War that separated evangelism and other spiritual activities from social action and ministry. Following the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Latin America became divided between those who saw the revolution as a “symbol of justice and liberation” and those who saw it as a “symbol of tyranny and . . . chaos.”43 At the same time, traditional Liberalism in Latin America died out, leaving Protestants without their longtime political allies. Meanwhile, Latin American societies underwent rapid secularization and industrialization, often resulting in greater economic dependence on the North and greater economic disparity at home.44 Adrift in a polarized political landscape, Latin American Protestantism itself began to divide between “those who felt that the ministry and preaching of the church should still be what it had been for generations” and those who “insisted that the new revolutionary times required that the church be present in the revolutionary process.”45 Some ended up concluding that the church should separate from the world, while others advocated for more intensive social involvement.46 It was a politicized, contextualized version of the dualism debate that had engaged the Christian church for centuries.

“I asked the Lord to provide me with food to feed my children”: A Holistic Theology Emerges in the Chocó

Despite the pressure within Latin American evangelicalism to define the gospel as primarily oriented to either spiritual or social concerns, Mennonite Brethren in the Chocó embodied and articulated a Christian faith that refused to separate the spiritual from the physical. Given the very real pressures of poverty in their context, food—obtaining it, eating it, and sharing it—became both a metaphor of holistic faith in Jesus Christ and a concrete and physical profession of that same faith among Chocoano Mennonite Brethren.

Victor Mosquera joined the Mennonite Brethren church in the village of Noanamá, although he later moved to Istmina and spent the majority of his years as a member of the church there. Like many who remember that period, Mosquera divides the first twenty years into pre- and post-John Dyck eras, because of the shifting emphasis to a “purely spiritual” gospel.

Because after John died in the plane accident, another missionary came who didn’t share the same vision [Dyck had]. . . . I continued with the church, not because of who [the missionaries were] but because of the Bible. He [the missionary] told them that they followed the church because of food. Ha! So many left, because those opportunities weren’t there anymore.47

Far from affirming this shift, however, Mosquera laughs, suggesting that it was foolishness to try and separate believers’ physical needs from their spiritual ones. In Mosquera’s analysis, it was not necessarily an indictment that some followed the church “because of food.” People came to the church because they found food there—literal food, as well as the health, education, and meaningful work—to feed their bellies as well as their souls. Mosquera admits that some may have joined the church because it was economically advantageous, but he also implies that the content of the gospel as preached by the missionaries had changed in the wake of Dyck’s death and centralization in Cali. A gospel that could not take into account the daily needs of Chocoanos was simply less attractive and relevant for many.

Over time, a practical theology emerged in the Chocó that joined the material and spiritual together into one gospel. In some cases, believers even included stories of material providence—of finding food to eat—as part of their conversion narratives. Eduardo Córdoba first came to hear the gospel from his brother, who had joined with the Mennonite Brethren church in Andagoya, a village downriver from Istmina. Córdoba made a decision to join the church and had even started to go through the pre-baptismal classes, but he still found himself wrestling internally with this new faith.

[We were going through] a very hard time of famine, and one night I asked the Lord to provide me with food to feed my children . . . and I began to go to the church early each morning at 5:00 to pray. And so I was walking through the street on the way to the church [and I ran into something] plastic and I picked it up. It was still dark, so I didn’t open it up to see what it was.

When I arrived at the church, I said to myself—well, at this time I was working for the Chocó Pacífico mine, but for the past four or five months they hadn’t paid me. And there was so much hunger, so much, and when I opened [the package], I looked and saw what the Lord had done for me because of my prayer; it was more than a month’s salary, a little bit more. And I was afraid to spend it, because I said, “Maybe someone lost this.” So I asked a vendor who was across the street from me if he had lost anything, and he told me no. So I said, “Well, this is a gift from God, and he has provided me with the money, more than one month’s salary.” This was the first miracle after I had identified myself with the gospel.48

Córdoba claimed that the miracle of finding money to feed his children had reaffirmed his faith in a time of questioning and doubt. For him, and for many others, there was no way to “look beyond this life level” and “grasp the spiritual implications,” because the physical hunger of their children and an unjust work situation were indeed profoundly spiritual matters. Until Córdoba was able to affirm that the needs of his family for daily food and monthly salary were considered by this new faith he had claimed for himself, he was not able to fully embrace it.

Américo Murillo, a young man in this period, became the pastor of Bebedó in 1965. Reflecting on the gap between missionary approaches in the 1960s and the daily reality of many believers, Murillo reflected:

For all the years that the missionaries were here, they could have done more to strengthen the national leadership, but . . . I don’t know, they lacked the vision [of the kind of] holistic gospel that we needed. Like what you see today, there is more energy [in that direction], towards the community, because Jesus said, he produced a whole gospel. He gave health and food as part of the goal of his mission, of salvation. That salvation includes health, food, and all that [we need].49

Here Murillo articulates that it was not only that Chocoanos needed a holistic gospel that took their hunger into account but also that Jesus himself had preached and lived such a gospel, that food is part of the salvation Jesus offers. Murillo’s reflection, offered with the benefit of forty-five years of hindsight, exemplifies the kind of theological work that emerged from this period.

In the years following this shift, there was a bit of a vacuum in the Chocó. One model—a model with admittedly many problems—had been removed, but believers did not find its replacement satisfactory. Initially, churches saw their attendance drop, sometimes dramatically. Victor Mosquera remembers a period in the 1960s when the core group in Istmina numbered only six men and women. But, recalls Mosquera, “We said to ourselves, ‘We cannot allow the church to die.’ . . . We took charge of the missionary house, and every Sunday, however few there were, we gathered and studied the Bible together. And from there on out, well, people became more and more encouraged.”50 As they regrouped, the congregations in Chocó began to create their own practices for expressing a holistic faith grounded in the congregation rather than the mission. In these years, the sharing of food both attracted people to the church and evolved as an outreach ministry in many congregations.

Pastora Torres Murillo was a young woman living in the rural village of Bebedó in the 1960s. Although there had been a Mennonite Brethren community in Bebedó for many years by this time, it was not until Torres heard a presentation by a female Chocoano missionary in 1967 that the church caught her attention. Soon after, she started associating with the women’s society and was baptized a number of years later. When asked how she came to know the gospel, Torres recounted the ways in which the church enacted community.

There was good organization, true fellowship in the church. The church worked together; if there was a believer that needed work, the church would help out with that. There was a unity, a fellowship. If I was in need, if I didn’t have anything to eat, if I needed bread, this believer would notice that I was lacking and would go and give me help. The church would extend a hand if I or any other believer was sick; the church was always there to help that believer get to the doctor.51

Torres encountered the gospel as both deeply spiritual and material, without any division between the two. Unlike earlier periods, however, her experience of a holistic gospel came through participation in her local congregation rather than through mission institutions or projects. Torres, in turn, helped initiate a food basket ministry in the village of Bebedó during her years on the congregation’s leadership team. The way church members shared their food with each other drew her into the church initially, as a testament to the holistic nature of the gospel, and eventually became a way that Torres ministered to others.52 The ministries of the congregation did not end with food, however. In the 1970s, for example, the church formed a cooperative that distributed loans to members and initiated the construction and operation of a day care center, where mothers could safely leave their children while they were mining out in the river.53 Bebedó and other Mennonite Brethren churches emerged from the 1960s and 1970s with new practices that authentically reflected their understanding of a holistic gospel, one that was embodied within the gathered community rather than mission institutions.

When the first Mennonite Brethren missionaries arrived in the Chocó, they presented a gospel wrapped in all the trappings of their own culture. Yet Chocoano believers received the message by passing the message back and forth through the lenses of their experience and of scripture. In this process they often used food, a mundane necessity of daily life, to test and articulate the gospel’s resonance in their lives, slowly constructing a theology that would be able to stand up to the poverty and injustice of their context. When cut off from all institutional support by religious persecution during La Violencia, Chocoano believers used food as a metaphor to resist armed police authorities and to define the essential practices of their faith community. Later on, when the mission advocated a dualistic gospel that reflected widespread polarization within Colombia and Latin America, food served as both evidence and metaphor in their emerging theological constructions. It appeared in their conversion stories, in their reflections on the meaning of the gospel, and in the congregational ministries that evolved to reflect their theological convictions. Although disadvantaged and severely limited by a historical lack of access to many of the state’s resources, the Mennonite Brethren communities in the Chocó used the most common of daily experiences—experiencing hunger and eating food—to articulate a holistic theology that spoke to the spiritual and material needs of their context. Their “hunger for the Word” led them to see Jesus’s salvation as a whole gospel that, in Américo Murillo’s words, includes “food and all that we need.”

Footnotes

Elizabeth Miller worked with Mennonite Central Committee in Colombia from 2009 to 2013 as a historian focused on the history of the Colombian Mennonite Brethren and Mennonite churches.

Jacob Stringer, “Colombia Poverty Figures Show Harsh Regional Inequality,” Colombia Reports (January 3, 2013), accessed March 22, 2015, http://colombiareports.co/colombia-govt-poverty-figures-show-harsh-regional-inequality/.

In this paper, Chocoano refers specifically to Afro-Colombians from Chocó.

For discussion on matrifocal nature of Chocoano society, see Aquiles Escalante, La Minería del Hambre: Condoto y la Chocó Pacífico (Barranquilla: Colombia, 1971); and Peter Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture: The Dynamics of Racial Identity in Colombia (Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins University Press, 1993).

Escalante, La Minería del Hambre, 29; Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture, 99.

Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture, 99.

Caroline Williams, Between Resistance and Adaptation: Indigenous Peoples and the Colonization of the Chocó, 1510–1753 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005), 156.

Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture, 99–100.

Mario Diego Romero and Kris Lane, “Miners & Maroons: Freedom on the Pacific Coast of Colombia and Ecuador,” Cultural Survival 25, no. 4 (2001), accessed January 26, 2012, http://www.culturalsurvival.org/

ourpublications/csq/article/miners-maroons-freedom-pacific-coast-colombia-and-ecuador.

Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture, 104.

Ibid., 108.

See “Ritual Mortuorio en el Pacífico Colombiano,” in Tradiciones religiosas afrocolombianas: Celebrando la fe desde la cultura, eds. Ayda Orobio Granja et al., (Popayán, Colombia: Corporación Centro de Pastoral Afrocolombiana, CEPAC, 2010); and Ivonne Maritza Sánchez Yap, “‘Id y haced discípulos a todas las naciones’: Estratégias de trabajo, evangelización, crecimiento y aceptación del protestantismo: Explorando el caso de las iglesias protestantes de Quibdó” (master’s thesis, Universidad de los Andes, 2005).

Republic of Colombia, “Censo de Población de 1951: Departamento del Chocó,” (Bogotá: Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística, 1955), 10. The census report was created by Jorge Saenze Olarte, Jesús Megarejo Rey, and others.

Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture, 102.

Ibid., 128.

J. J. Toews, The Mennonite Brethren Mission in Latin America (Hillsboro, KS: MB Publishing House, 1975), 88.

Early converts were predominantly male, a fact which perhaps demonstrated a lack of resonance between the Mennonite Brethren message and matrifocal Chocoano society, especially considering that most religious movements count a higher percentage of female participants in the initial stages of growth.

For one example, see Colombian News and Views 1, no. 3 (December 1950).

Colombian News and Views 1, no. 3 (December 1950).

Juana B. Bucana, La Iglesia Evangélica en Colombia: Una historia (Bogotá: Asociación Pro-Cruzada Mundial, 1995), 134.

James E. Goff, “The Persecution of Protestant Christians in Colombia, 1948 to 1958, with an Investigation of Its Background and Causes” (ThD diss., San Francisco Theological Seminary, 1965), 237; 170–79.

“Minutes of the Meeting of the Missionary Council,” June 11–14, 1956, Mennonite Library and Archives, A250–13 Missionary Council 1954–1956.

Carmela Mosquera de Martínez, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 26, 2010.

“Minutes of the Meeting of the Missionary Council,” June 10–15, 1957, Mennonite Library and Archives, A250–13 Missionary Council 1957–1960.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Dagoberto Minota, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 29, 2010, translated from Spanish by the author.

Victor Mosquera, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 26, 2010.

Wade, Blackness and Race Mixture, 45.

Victor Mosquera, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 26, 2010.

Dagoberto Minota, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 29, 2010.

“Minutes of the Missionary Council,” June 11–14, 1956, Mennonite Library and Archives, A250–13 Missionary Council 1957-1960; and “Minutes of the Missionary Council,” July 4–8, 1960, Mennonite Library and Archives, A250–13 Missionary Council 1957–1960. The population of Istmina was less than 3,000 in these years.

See interviews with Victor Mosquera, Dagoberto Minota, Luzmila Rumié, and Hernán Mosquera.

Hernán Mosquera, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 28, 2010, translated from Spanish by the author.

Vernon Reimer, “Mennonite Brethren Theological Education in Colombia, 1946–1969,” (paper prepared for J. J. Toews for textbook on Mennonite Brethren missions, January 1970), Mennonite Library and Archives, A250–13 Vernon Reimer, 1966–1977, 7.

Ibid.

Reimer, “Mennonite Brethren Theological Education in Colombia, 8; see also “Missionary Council Minutes,” Nov 25–28, 1957, Mennonite Library and Archives, A250–13 Missionary Council Minutes 1957–1960. By November of 1957, only three of the Mennonite Brethren missionaries working in Colombia had been with the mission previous to that year and had experience living and working in the Chocó.

Gabriel Mosquera, interview by Sarah Histand, April 19, 2007, translated from Spanish by the author.

Ibid.

Letter from Alvin Voth to Marion Kliewer (Hillsboro, KS), January 28, 1964, Mennonite Library and Archives, A250–13 Alvin and Vera Voth 1964–1966.

“Missionary Fellowship Minutes,” Jan 7–8, 1963, Mennonite Library and Archives, A250–13 Missionary Fellowship 1961–1965.

Idina E. González and Justo L. González, Christianity in Latin America: A History (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 234.

Pablo Alberto Dieros, Historia de Cristianismo en América Latina (Buenos Aires: Fraternidad Teológica Latinoamericana, 1992), 779, 799.

González and González, Christianity in Latin America, 234.

Dieros, Historia de Cristianismo, 800; González and González, Christianity in Latin America, 249.

Victor Mosquera, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 26, 2010, translated from Spanish by the author.

Eduardo Antonio Córdoba Guebara, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 27, 2010, translated from Spanish by the author.

Américo Murillo, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 29, 2010, translated from Spanish by the author.

Victor Mosquera, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 26, 2010. Translated from Spanish by the author.

Pastora Torres Murillo, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 27, 2010, translated from Spanish by the author.

Ibid.

Américo Murillo, interview by Elizabeth Miller, January 29, 2010; Executive Committee Meeting, Acta No 008, December 12, 1975, Office of the Igleisa de los Hermanos Menonitas de Colombia, Colegio Américas Unidas.