Introduction

Faced with the tension between the particularity of Jesus Christ and the plurality of cultures and religions, it is increasingly necessary to develop a robust theological account of cultural diversity within the world church.1 I will use the concept of translatability—the affirmation that the gospel can be expressed in the terms of any human culture—as a handle with which to approach this task. While discussions of translatability are often associated with mission historians or Bible translation scholars, I believe translatability can also be a fundamentally useful concept for understanding global Christianity, and for responding to the challenges of a globalizing, yet post-Christian West. While I will focus on cultural diversity within the church, questions about the theological importance of cultural diversity are also relevant to a theology of religions, especially in today’s context of pluralism and relativism. Discerning how to relate to people of other faiths requires wrestling with some of the same fundamental questions about the nature of culture, the nature of the church, and the role of diversity within the faith community.

Several examples from my personal experience illustrate how different ideas about the role of cultural diversity in the church can lead to conflict and alienation between Christians from different cultural backgrounds. As a “missionary kid” growing up in Papua New Guinea, I listened to expatriate missionaries justify the task of Bible translation through appeal to an eschatological vision of many peoples, tribes, nations, and languages praising God together, and began to wonder about the contrast between this discourse and the lack of regular common worship between expatriate and Papua New Guinean Christians living in the same community. While doing research for a master’s thesis in Burkina Faso, I saw that missionaries and church leaders disagreed about the importance of using a lingua franca in worship services or church meetings in order to facilitate comprehension.2 Missionaries pleaded that using the vernacular would ensure that the most vulnerable, the monolingual elderly women, would be included—but they mixed this with a discourse that essentialized the vernacular by equating it with culture or ethnic identity. Church leaders argued that focusing on vernacular literacy was a way to limit people’s options and that pushing for vernacular use in a church service led to exclusion of visitors and those of other ethnic groups, thus betraying the gospel. Yet both parties strongly affirmed that God’s word could and must be expressed in the vernacular. Finally, in Montréal I have attended churches that seem unable to drum up much interest in other cultures and peoples—and whose more established members confess to feeling insecure in the face of an influx of newer African and Haitian members and adherents. These cross-cultural struggles are not unique to my experience, but will find echoes among many who are committed to a culturally diverse church.

Each of these experiences has led me to ask why, in so many churches, we do not act like we believe that the hard work of developing cross-cultural relationships, and the work of resolving the inevitable cross-cultural conflicts that will result, are imperatives grounded deeply in the gospel itself.

They have motivated me to try to identify widely divergent assumptions about culture and identity, about plurality, and about the nature of church that may lurk behind a common discourse of translatability. Finally, they have led me to insist that an account of the plurality of cultures and languages in the church must move beyond affirmations of translatability, beyond challenges to pluralism and relativism and even beyond the incarnation, to a fuller exploration of the cross as an event that broke down barriers between groups of people and thus created a new humanity. Any account of plurality must foster the urgent conviction that Christians in a particular place, who come from different cultural backgrounds, must find ways to do church together across cultural boundaries.

I will begin by examining the accounts of translatability proposed by three different theologians. In some cases the translatability language is explicit, while in others it must be inferred from discussions about mission or church or culture. In this section I will show how similar-sounding discourses about the tension between the particular and the universal, and about the relationship between translatability and cultural diversity, may rest on widely divergent and even contradictory presuppositions and biblical underpinnings, leading to quite different understandings of how the multiplicity of cultures within the world church relates to the church’s identity and mission. In a second section, I will identify and engage with five specific factors that differentiate the accounts. These factors will form the framework for the development of a fuller account of cultural plurality within the church. Drawing most heavily on John H. Yoder,3 but including the ideas of other scholars as well as my own, I will suggest that the church is best understood as the true new humanity; moreover, because of the incarnation and the cross, we have a way of welcoming diversity within that body without succumbing to cultural relativism. Translation can then be understood as a way to integrate new cultures into the church, with the conversion of each culture and the reconciliation across cultural boundaries mutually reinforcing each other. I will conclude by making some practical suggestions and identifying some of the challenges that remain.

Part I: Talking about Translatability

Part I gathers together three relatively well-known accounts of translatability, pluralism, and the global church. Each of them discusses how the uniqueness of Jesus is related to the plurality of cultures, either inside or outside the church. All have in common a conviction that Jesus is Lord: all refuse (at least on the surface) a relativistic account according to which Jesus is one of many manifestations of a larger, universal truth about the divine. All moreover agree that the gospel can and must be translated into different cultural forms. However, it will become clear that they diverge significantly with respect to the role that cultural plurality plays in their account of the everyday practices of the congregation, their understanding of the nature of culture, the theological bases they propose for translatability, and the way they address the tension between the universal and the particular.

Lamin Sanneh: Culture as a force for the expansion of Christianity

Sanneh’s ground-breaking work, Translating the Message, is one of the most comprehensive treatments of the role of Bible translation in the growth of the church, with a particular focus on Western Africa during the modern missionary movement. Sanneh is concerned to demonstrate that mission and the destruction of local cultures by no means go hand in hand,4 but that, in spite of themselves, missionaries who translated the Bible into the vernacular liberated a force for cultural renewal and revitalization, and for the development of nationalist identities and sentiments.5 It is in support of this thesis that Sanneh develops his concept of translatability, based on both biblical and historical analysis.

For Sanneh, translatability is defined as follows: when Peter and Paul recognized that the gospel needed to be translated from its Judaic origins into a Gentile context, this involved a simultaneous affirmation both of the destigmatization of the target Gentile culture (and thus, of all cultures) and of the relativization of the source Jewish culture.6 Since then, no culture can be seen as a privileged vessel for communicating the gospel; but, at the same time, the particularity of each culture is affirmed.7

One of the most important contributions of Sanneh’s work is the recognition that since the gospel is always conveyed in cultural garb, it is worth paying much more attention to the role of the recipients of the message in their efforts to appropriate or translate the message into their own culture. This is an important corrective to the simplistic tendency to castigate missionaries for bringing a gospel clothed in western culture (as if they could have brought any other kind) and then assume that everything interesting has been said. Sanneh thus argues that even though “colonial co-option weakened Christianity by presenting it as a freshly minted European creed…Africans rejected that view by circulating the religion as local currency.”8

However, on closer examination, Sanneh’s account seems incoherent or inconsistent in several important ways. First, when it comes to providing a theological grounding for this view of translatability, Sanneh proceeds in an inconsistent manner. While he argues that culture is both destigmatized and relativized through the gospel, only the relativization of culture is given a biblical foundation, and a very sparse one at that. The destigmatization of culture, on the other hand, is justified on mostly extrabiblical grounds.

For Sanneh, cultures are relativized because God’s universal love transcends culture, such that faith has now become a purely personal, acultural matter. For example, Sanneh suggests that in Peter’s dealings with Cornelius, it was his recognition that “God is no respecter of persons” that “breached the walls of separation between Jew and Gentile.”9 Instead of drawing on Paul’s explicit teaching that the breaking down of the wall of separation between Jew and Gentile is grounded in Jesus’ work on the cross (Eph. 2:14), Sanneh instead repeatedly grounds this new relationship between Jews and Gentiles in the idea that God is above culture; and, since Jesus is one with God, human cultural differences no longer matter. For example, Sanneh argues that early Christians’ understanding that Jesus was actually God’s Exalted One “gave an otherworldly direction to Christian life and devotion, with faith in the absolute righteousness of God finding its corollary in the provisional, relative character of this world. This opens the way for pluralism by stressing the nonabsolute character and coequality of all earthly arrangements.”10 Sanneh also suggests that the relativization of culture, for Paul, was due to his understanding that “the center of Christianity…was in the heart and life of the believer without the presumption of conformity to one cultural ideal.”11 Sanneh’s more recent work reiterates this point.12 Clearly, if the only theological foundation for the relativization of culture is our recognition that God calls us to a purely inner faith that is unrelated to our social organization, then it becomes difficult to imagine what relevant role is left for culture to play in the church.

Interestingly, Sanneh does develop a foundation for the dignity and importance of culture, but he does so mostly on an extrabiblical foundation. At a minimal level, reference to God’s non-partiality provides some dignity to culture because no one can say that their culture is inferior to anyone else’s; so in this way, Christianity provides a constant challenge to any claims for cultural exclusivity. However, mixed in with this basic affirmation are rather strange ascriptions of power and autonomy to cultures and languages themselves. It seems that for Sanneh, culture itself has a certain latent force that is somehow unlocked through translation. For example, by engaging in Bible translation, Sanneh says that missionaries let the “genie…out of the bottle”—a force was unleashed that they could no longer control,13 one that “endows persons and societies with the reason for change and the language with which to effect it.”14 Sanneh speaks of the vernacular as being like a weapon that “Africans…came to wield against their colonial overlords.”15 Going even further, he suggests that the existence of multiple cultures in the worldwide church, beginning with the overcoming of the barrier between Jew and Gentile, is actually due to the power of culture and language, rather than to the power of the gospel: “As the religion resounded with the idioms and styles of new converts, it became multilingual and multicultural. Believers responded with the unprecedented facility of the mother tongue, and by that step broke the back of cultural chauvinism as, for example, between Jew and Gentile. Christianity’s indigenous potential was activated, and the frontier beckoned.”16

Second, along with this personification of culture and language comes a strong tendency to talk about saving or preserving cultures, whose basic goodness and validity he never really questions. The missionary plays an important role in this process as he or she tends to become interested in and fascinated by the beauty of other cultures.17 Sanneh claims that Paul’s encounter with Gentiles led to a personal experience of being able to relativize his own culture. In this way, he contributed to “indigenous revitalization.”18 For Sanneh, Paul “desired above all to safeguard the cultural particularity of Jew as Jew and Gentile as Gentile, though challenging both Jews and Gentiles to find in Jesus Christ their true affirmation.”19 Although it seems rather dubious to project a concern for cultural preservation onto Paul based solely on the observation that he wanted Jew and Gentile to express their faith authentically within their culture, Sanneh uses this to justify a much broader general agenda for cultural preservation apart from the church.

Third, the church is strikingly absent as a relevant social grouping affected by translatability. In Sanneh’s romantic appeals to the idea of the cultural “frontier,” the missionary plays a surprisingly central role as the carrier of a disembodied entity that he calls “Christianity,” and as the source of indigenous renewal through his or her special role of initiating translation and recognizing the intrinsic value of other cultures. This is completely divorced from questions of the social shape of the church and of its role as a place where cultural differences may be wrestled with and overcome. In defining translatability, Sanneh is not attempting to account for the reconciliation of Jew and Gentile into one body, but only for the legitimacy of Jews and Gentiles being able to express the gospel in the terms of their own culture and language. He is saying nothing about the relationship between cultures in the church, just that any culture and language can be used for faith purposes. The most relevant social realities for Sanneh are the groups of those who share a culture or language—hence his frequent references to indigenous renewal and nationalist sentiment.

Fourth, even as Sanneh affirms the particularity of local cultures, there is a strong universalizing current to his thought that ironically undercuts this concern. Particularity is presented as a contribution to a more universal reality, for example through his claim that “particular Christian translation projects have helped to create an overarching series of cultural experiences, with hitherto obscure cultural systems being thrust into the general stream of universal history,”20 or through his image of a “universe of cultures” with God in the middle.21 Pluralism is seen as a good in its own right, with Bible translation being a mechanism for releasing “forces of pluralism” into the “culture.”22 Thus in the end, culture for Sanneh is a concept that is ironically abstracted away from the real particularities of local settings.

In conclusion, Sanneh’s views boil down to cultural relativism. He sees God’s universality—his being above culture—as the basis for translatability, without any reference to the particularity of Jesus in his life or his death. Culture for Sanneh is a second basis for translatability: it is personified as an autonomous and powerful force, ironically divorced from local realities, that is awakened through Bible translation and ends up driving the expansion of Christianity. As I have argued elsewhere, this is bound up for Sanneh with a strong equation of language and culture, and with a distinction between vernacular language and other, to him inferior, languages of wider communication.23 The social groupings to which this theory relates are indigenous peoples and missionaries as privileged agents of translation, while Christianity as an entity is abstracted away from church bodies or congregations.

Andrew F. Walls: The church as full-grown humanity

Although translatability as a concept is often associated with Sanneh, Walls provides by far the more detailed and explicit discussion of it. Grounding his presentation firmly in the incarnation, in the apocalyptic vision and in the Ephesians image of the full stature of Christ, he makes a unified and coherent case not only for the need for multiple cultural perspectives in the church, but also for relationships across cultural boundaries. However, he leaves a few important questions unexplored when it comes to the cross, the practices constitutive of the new humanity, and the nature of culture.

The incarnation is fundamental for Walls as the basis for translatability, the source of both diversity and unity in the church, and as a protection against relativism. Walls argues that the incarnation is the original translation of God’s word into a particular human setting in Jesus, despite the riskiness and even impossibility of the translation enterprise.24 At the very heart of our faith is the recognition that Jesus came as a person into a particular culture; Jesus accepted “that taking a seat in the theatre of life means taking a particular seat.”25 This original act of divine translation provides the rationale for Bible translation as well as for the generations-long process of conversion not just of people but of cultures or “national distinctives,”26 and even of nations.27 The process of conversion of communities or nations (not just individuals), that is, the long process of bringing the former cultural system “into relation with the word about Christ,”28 will lead to diverse outcomes because it is a turning of what is already there, a transformation rather than a substitution.29 Thus, he argues that “Christian diversity is the necessary product of the incarnation.”30 Yet because there is an original act of translation in Jesus, different translations of the gospel have a firm source version that leads to unity between these cultural expressions by ensuring coherence between various translation attempts.

Translation takes place at the intersection between the universal and the particular, since the irreducible particularity of the source or target text is juxtaposed with the fact that translation is possible at all. To address this tension, Walls proposes two principles that must both be adhered to. The “indigenizing” or “homing principle” is based not on God’s universality but on the recognition that Christ came into a particular culture, making it possible for the gospel to be at home in any culture. In contrast, the “universalizing” or “pilgrim principle” is the recognition that there is only one Christ.31 This explains why faith communities from different cultures exhibit a “family resemblance,” and causes Christians to live in tension with their surrounding society, knowing that they are not ultimately at home there.32 The two principles can be summarized as follows: “The Church must be diverse because humanity is diverse. The Church must be one, because Christ is one, embodying in himself all of the diversity of culture-specific humanity.”33

In addition to drawing on the incarnation as the justification for cultural diversity within the church, Walls also develops other New Testament images in order to account for the necessity not just of a multiplicity of culturally homogenous churches, but of cross-cultural relationships both between and within these bodies. First, by drawing on the Revelation vision of the church as a city with doors open on all sides to the riches of the nations and on Ephesians images of the church as a temple and a body,34 Walls argues that the contributions of all cultures are necessary in order to attain to the full stature of Christ.35 Cultural expressions of the faith, or “converted lifestyles,”36 are building blocks for an eschatological worldwide church or temple or body that has attained the “full stature of Christ,”37 or “the Full Grown Humanity” of Ephesians.38 Second, it is not enough for Walls to see these “culture-specific segments” as free to exist in isolation of each other,39 each enjoying its authentic converted lifestyle alone without relating to Christians of other cultures.40 As the New Testament documents show, it was essential for the apostle Paul that the “two races and two cultures historically separated by the meal table now [meet] at table to share the knowledge of Christ.”41 For Walls, this necessity of eating together—despite the cultural barriers that prevented circumcised and uncircumcised persons from doing so—derives from the fact that neither Jewish nor Gentile Christianity could be valid in isolation of the other. “Each was necessary to complete and correct the other; for each was an expression of Christ under certain specific conditions, and Christ is humanity completed.”42 Thus the necessity of breaking existing cultural rules in the church is grounded in Christ as the fulfillment of humanity.

One important contribution of Walls’ account is that he makes a clear distinction between language and culture. Translating the Bible into a language is not the same thing as translating the gospel into a culture. This distinction is important, since it speaks to the Burkinabè conflict from the introduction, illuminating the extent to which both Sanneh, and missionary Bible translators in that context, tend to conflate the vernacular with cultural identity. Walls clarifies that what really matters is that the Word takes flesh in different contexts; and by providing two contrasting historical examples, he shows that this may or may not include the use of a vernacular language in every area of church practice. Thus, while he emphasizes the importance of the vernacular, there is also a place for languages of wider communication to serve as languages of unity.43

I would identify three potential shortcomings in Walls’ account. First, while Walls clearly longs for true “fellowship across the broken middle wall of partition,”44 it is still not fully clear to what extent the ideal is a multitude of fully converted monocultural churches, many of whose members relate to each other regularly, or a struggle to overcome cultural divisions in every local congregation, even if that might prevent adherents of one culture from having the space to work out without interference the implications of conversion just in their own culture. Walls sometimes makes it seem a little too easy, as if just the fact that other churches exist somewhere out there might be enough: “it is a delightful paradox that the more Christ is translated into the various thought forms and life systems which form our various national identities, the richer all of us will be in our common Christian identity.”45 As a result, it sometimes remains ambiguous to what extent the redeemed and culturally diverse body itself is the most relevant category for Walls, in contrast with the converted nation or people.46

Second, Walls’ view of culture seems slightly too neutral. In his exposition of the church as a new structure or body that is made up of converted cultural segments, he does not sufficiently develop the question of how to critique elements of culture within this new structure. Thus the “acid test” of the meal table,47 while a crucial contribution to this discussion, was a tantalizing one that left me hoping for a clearer explanation of how the redeemed body develops practices that allow it to transcend the rebellious aspects of culture.

Finally, it seems to me that Walls does not develop the event of the cross quite fully enough in order to clarify precisely how Jesus’ death caused the breaking down of the barrier between Jew and Gentile. When he talks about the dividing wall broken at the cross, he does refer to the “union of irreconcilable entities…brought about by Christ’s death.”48 But Walls seems to focus more on the way that the decision of the Jerusalem Council not to enforce the Torah for Gentiles was the act of breaking down this barrier,49 rather than grounding it in something that happened on the cross.

To summarize, Walls’ definition of translatability as grounded in an original act of divine translation provides a much more satisfying rationale than Sanneh’s for the subsequent translations both of the Bible into diverse languages and of the gospel into diverse cultural expressions. He wants to account for the need of converted peoples to relate to each other, not just to check and improve each other’s translations, but to be built into a full-grown humanity. Thus he gets at the idea of a new entity that is made up of groups of people whose cultures are converted, calling this a full-grown humanity or an expression of the full stature of Christ. For Walls, the goal seems to be about having Christ expressed more fully, as each converted culture brings the best it has to the new city or body. His exploration of Pauline and apocalyptic literature for teaching about the relationship between “culture-specific” segments of the body opens many interesting avenues for reflection. However, questions still remain about the exact relevance of the cross-event for Walls to the constitution of the new humanity. His account also still leaves us hoping for a clearer rationale of why the culture-specific building blocks of the global body need to relate to each other. Finally, while his focus on “conversion” presupposes the idea of cultural critique, his neutral attitude toward culture leads him to frame conversion in a mostly positive way, more like bringing out the best of what is already there, rather than struggling to turn an inherently rebellious structure toward Christ.

John Howard Yoder: Hammering culture into submission within the new humanity

Yoder makes three important contributions to the debate. First, instead of being predisposed to affirm culture’s intrinsic value, he tends to evaluate cultural practices in terms of their faithfulness or rebelliousness. Second, the ideal of cultural plurality in the church is grounded firmly in the reconciling work of Jesus on the cross. Thus Yoder is able to develop a unique perspective on translatability that sees it as a process of cultural conversion inseparable from the reconciling practice of the new peoplehood that is the church. Third, this account seems to overcome the tension between the universal and the particular in a more satisfactory way than the other accounts.

While the diversity of cultures, for Yoder, derives from God’s divine intention from creation (Acts 14:16; 17:26),50 there is nothing particularly sacred about culture itself. On the contrary, cultural assumptions, and even language,51 are among the rebellious powers that have a “vested interest in keeping peoples separate and alienated from one another.”52 What matters is being able to judge if a given cultural form is right and faithful or not. Yoder also points out that cultures do not convert as a whole: the transformation of culture through the gospel will usually include a split or conflict between those who are being transformed by the gospel and those who are not—yet both groups belong to that culture.53 He thus moves away from any personification or essentialization of culture toward seeing culture as an imperfect structure that can be partially redeemed to the extent that some of its actors are willing to participate in the new humanity, thus transcending the ways in which cultural structures tend to reinforce divisions and injustice between people.

At the same time, Yoder in no way denies the rootedness of the gospel in particular cultures, but rather emphasizes that no “acultural” gospel can exist.54 His affirmation of particular, historically contingent culture as a valid (and indeed the only) “skin” for the gospel is based on the incarnation in a way that resembles Walls’ account.55 For Yoder, the incarnation demonstrates a unity of medium and message, since “when God wanted to communicate with us, God had to come among us.”56 Thus Yoder insists that it is a mistake to believe that particularity can be transcended.57 The possibility of translation is grounded in the “ordinariness” or historical particularity of Jesus that “frees us to use any language, to enter any world in which people eat bread and pursue debtors, hope for power and execute subversives. The ordinariness of the humanness of Jesus is the warrant for the generalizability of his reconciliation.”58

Building on his view of culture as rebellious, Yoder develops a concept of translation or “cultural transition” that is similar to Walls’ idea of conversion, but with a more conflictual tone.59 In an analysis of five New Testament cases in which the apostles try to proclaim the message of Jesus in the terms of a particular cosmology (such as the gnostic or Athenian worldviews), he emphasizes that their strategy is always to use the language of that cosmology, but to refuse to fit Jesus into a slot in that cosmos. Instead, they always insist that Jesus is Lord over that cosmology, but that his lordship has been attained through suffering. Yoder’s emphasis differs from Walls’ here: he is not saying that the gospel can be translated out of one particular world into other particular worlds because all worlds are essentially equivalent. Rather, translation is the act of seizing culture from within and making it serve Christ. Yoder’s account of the early Christian attempts at translating Jesus into other cosmological terms suggests that translation required a lot of nerve. This small group of Jews “refused to contextualize their message by clothing it in the categories the world held ready. Instead, they seized the categories, hammered them into other shapes, and turned the cosmology on its head, with Jesus both at the bottom, crucified as a common criminal, and at the top, pre-existent Son and Creator, and the church his instrument in today’s battle.”60

This audacity was based on the conviction that they did not need to “join up with, approve, and embellish with some correctives and complements” the wider world, but to proclaim the “Rule of God.”61 While this may seem to lead to an anti-cultural stance, it does not; rather, because the rule of God is seen as the basic category, these early translators could relate to cultural systems, cosmologies and other powers as having already been defeated, but also “reenlisted” to serve God’s purposes.62 Thus culture is both relativized and valorized. Culture has value, but only to the extent that one can find a way to confess, in the terms of that culture, that Jesus is Lord—even when cultural categories tend to rebel against letting one make that affirmation.

Both Sanneh and Walls note that the gospel’s first boundary crossing, or translation, occurred when Jews began to welcome Gentiles into the church. Walls notes a connection in Paul’s teaching between the overcoming of the barrier between these two cultural groups, and the event of the cross. However, only Yoder provides an account of exactly how Jesus’ death accomplished this reconciliation. In Yoder’s view, the cross shows us Jesus’ complete rejection of any logic that would limit “love” to “one’s own”—i.e., to those who share a cultural, ethnic or national identity.63 Rather, the full “scandal of the cross” is that no lives, even the lives of aggressors and enemies, are worth less than other lives,64 and therefore, using force to usher in the Kingdom would breach the harmony of medium and message that existed in Jesus.65 Jesus’ life thus demonstrated the possibility that one can be fully human and rooted in a culture, yet reject any cultural logic that would make necessary the sacrifice of some in order to be “effective in making history move down the right track.”66 His death demonstrated the world’s rejection of this stance, while his resurrection was God’s vindication of his radical “willingness to sacrifice in the interest of nonresistant love, all other forms of human solidarity.”67 Thus at the cross Jesus decisively demonstrates a new way of being fully human.

This understanding of the cross makes it clear exactly how Christ’s death abolishes the wall of separation, that is, the rebelliousness of culture. Yoder argues that Paul, in 2 Corinthians 5, is responding to those who criticized his practice of making Jews and Gentiles pray and eat together in the church, rather than allowing them to do so separately.68 Paul’s response is based on the “inclusiveness of the cross”—the fact that Christ died for everyone leads to the end of discrimination, or of relating to people “ethnically.”69 As a result, one’s adherence to the new humanity is inseparable from the refusal to defend any form of cultural or national identity with force. This may explain why Yoder exhibits little to no sense of need to preserve a cultural grouping for its own sake. Instead, he insists that Paul’s message of true equality is “rooted not in creation but in redemption”: it is because Christ died for all that a new way of relating across social boundaries is possible, whereas creation from the beginning divides people “among tribes and tongues and peoples and nations.”70 Another way of saying this is that in Christ, a “new phase of world history” has begun: the church can be called “a ‘new world’ or a ‘new humanity’…because its formation breaches the previously followed boundaries that had been fixed by the orders of creation and providence.”71

Yoder’s understanding of the cross allows him to address the tension between the universal and the particular in a clearer way by providing a stronger version of the pilgrim or the relativizing principle than what Walls and Sanneh can provide by basing their account either on the incarnation or on God’s lack of partiality. For Yoder, though the possibility of translation derives from the incarnation, its necessity derives from the cross; to state this using Walls’ terminology, one can only be truly at home in a culture (indigenizing principle) if one participates in the new humanity that profoundly relativizes cultural claims (universalizing principle). Yoder’s “new humanity” resembles Walls’ concept of “full-grown humanity,” except that it is more clearly defined as being intercultural even at the local level, rather than being a supra-cultural body that includes many monocultural social bodies within it. Thus the two extra pieces that Yoder brings to the puzzle—the rooting of cultural relativization in the cross, and the perspective of culture as fallen and needing redemption—allow the indigenizing and pilgrim principles to relate to each other in a clearer way.

Yoder’s account has several important implications for the church’s mission strategy. First, because the cross constitutes this event of breaking down boundaries that divide, the existence of the new humanity must be understood as inseparable from its message. He argues strongly that “if reconciliation between peoples and cultures is not happening, the Gospel’s truth is not being confirmed in that place”72 and that the “new peoplehood…is by its very existence a message to the surrounding world.”73 Therefore, since the message is not disembodied but is carried by a community, it is translated into new settings not in the way that a seed is planted, but as a new shoot is grafted into an existing plant. This occurs through the opening of one’s cultural identity to outsiders in concrete practices of fellowship at the meal table, reconciling dialogue, and the recognition of the gifts of each one. Because of the incarnation, identity did not need to be “smashed.” But because of the cross, it “needed to be cracked open.”74 In this view, the process of translation itself can be understood as the constant breaking open of local manifestations of the new humanity to welcome yet another culturally defined group to the concrete, actual meal table in order to have that group, too, express Christ’s lordship in the terms of its own cosmology.

Second, as the gospel moves into new cultural settings, it is not primarily abstract concepts, but practices and guidelines, ordinary social forms and realities that must be translated into the new setting. This does not mean that “forms” are translated while an acultural “essence” remains the same. Yoder rejects the idea that some cultural elements are essential and others are secondary, unimportant, or “just” formal. Noting that Peter and Paul disagreed about table fellowship, which was clearly a matter of form and yet considered essential to the gospel, he reminds us that content and form cannot be distinguished that easily.75 Since the church in its social and political specificity is a foretaste, a paradigm, of the way the entire world is called to live,76 its specific practices must be translatable into various cultural contexts. Thus, if the body is constituted through what he has called sacramental or evangelical practices—such as eating together, baptism, reconciling dialogue, the involvement of all community members in church business, and the multiplicity of gifts in the church77—then such practices are “procedural guidelines,” flexible enough to be adapted to any culture.78 They should be able to be practiced in a way that includes people from different cultures practicing them together. This is easiest to see for eating together, since the early church conflict about the inclusion of Gentiles was centrally about their inclusion in the meal,79 but would apply to the other practices as well.80

Third, because the cross creates a new intercultural humanity, we must be able to identify the specific cases where cultural sensitivities must be offended because they threaten “the inter-cultural quality of the Messanic [sic] community.”81 This is not a denial of the importance of proclaiming the message in ways that are not unduly alien,82 but a reminder that, as in the early church conflict about table fellowship between Jews and Gentiles, the gospel speaks to the need for offending homogeneities because of the cross. Thus Yoder strongly rejects a conscious church growth strategy aimed at the creation of ethnically homogenous churches.83

Fourth, because of the importance of the new peoplehood as being both the message and the medium for communicating it, Yoder suggests that we take a cue from Paul’s missionary strategy. Paul, he argues, never planted a new community from scratch by bringing together individual converted Jews and Gentiles. Instead, he always began his proclamation with the existing synagogue.84 Those from the synagogue who accepted his message then formed the “sociological base” that was opened to Gentiles: “There was a community before there were converts.”85 This contrasts, of course, with modern mission strategy, where we “do carry a message without a synagogue.”86 This observation has led Yoder to propose a mission strategy that he calls “migration evangelism,” worked out most fully in the 1961 pamphlet, “As You Go.”87 While I believe this method needs significant updating and refinement, it does have the great advantage of trying to overcome the major shortcoming of modern missions, namely that the more mature, sending church believes it has “the right to lob the message over the cultural fence rather than associating [itself] deeply with the host culture.” This tragically causes the sending church to miss out on truly experiencing the “foretaste of the heavenly choir from every tribe and tongue and people and nation” through a focus on how the new Christians must change, without being willing to change itself.88 Through an analysis of New Testament literature,89 Yoder suggests that Paul required the Jewish “senior believing community” to make the more significant changes to their cultural dietary practices in order to open their table fellowship to include Gentiles.90

One element of Yoder’s account that still seems incomplete is the relationship between diversity and particularity in the church. Yoder’s account does not quite make enough room for Walls’ insight that each redeemed culture contributes to showcasing Christ more completely. Yoder sometimes seems to emphasize reconciliation even to the point where cultures might lose their particularity in order to form the new (though still particular and historical) people of God. Surely the image of the church as a city in which riches from all nations are brought in must presuppose some space for adherents of each culture to work at the redemption of their specific culture, even while they engage in reconciling dialogue with those of another culture. Yoder doesn’t clarify sufficiently where this space might be found.

To sum up, Yoder comes at the question of translatability primarily via discussions about the tension between the particularity of Jesus and the pluralistic or relativistic worldview, and also via an overarching concern to exposit the church, both local and global, as constituting a new humanity established at the cross. Because he tends to see culture as a “power” in rebellion against Christ’s lordship, he associates translation with the act of seizing a cosmology or worldview and making a confession of Christ’s lordship possible within this frame of reference. The basis of translatability for Yoder is not that languages or cultures are simply neutral and interchangeable because they were all created equal. Instead, translation is possible only because at the heart of Jesus’ message of reconciliation was the medium of coming and identifying with the ordinariness of a particular culture and place.91 And yet, the cross remains central to Yoder’s account: faithful translation cannot happen in isolation from the social structure of the new humanity created at the cross. It was there that Jesus demonstrated for the first time the possibility of being fully human in a particular cultural setting, while at the same time rejecting any cultural solidarities that would lead to the separation of peoples rather than their reconciliation. Thus any translation of the gospel that does not both derive from and lead to a practicing intercultural fellowship would not be a translation of the gospel at all, but of some “other gospel” (Gal. 1:8). In sum, translatability for Yoder could be defined as the redeemability of culture for God’s good purpose, through participation in the new humanity that has been inaugurated by the suffering triumph of Jesus in his particularity.

Part II. Towards a Constructive Account of the Global Fullness of Christ

In the anecdotes related at the beginning, I suggested that local and expatriate Christians on a Papua New Guinea mission station should place a higher priority on common worship, that the conversion of Québec culture in isolation from other cultural groups living in Québec is not enough, and that translation of the Bible into the vernacular need not lead to mono-ethnic churches in a multilingual West African context. At this point in the argument, it has become clear that theologians with different assumptions about translatability might not agree with me about each of these statements. One’s underlying assumptions about translatability are linked with concrete practical realities; thus, understanding these assumptions matters. In this section, I propose five criteria that capture the crucial differences between Sanneh’s, Walls’ and Yoder’s accounts. I then engage with each criterion in order to move closer to a theologically robust account of translatability and of cultural diversity in the global church.

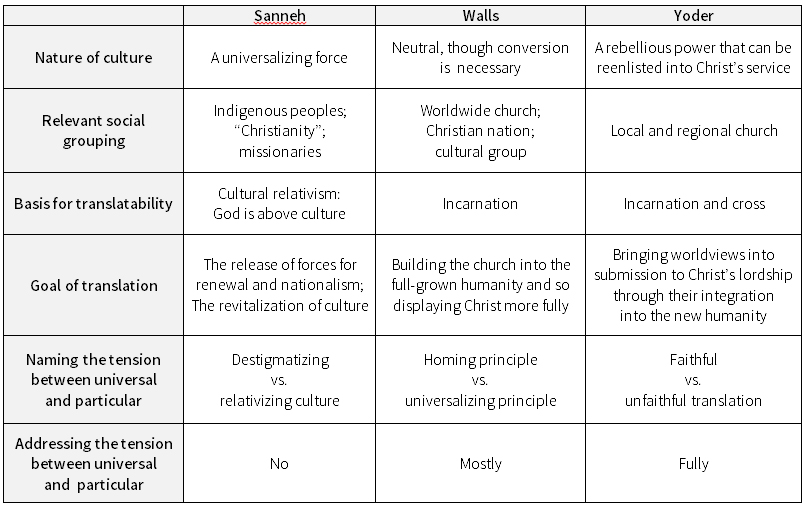

As we move through the discussion, Table 1 will facilitate comparisons between the different authors along these five dimensions.

The nature of culture: an understanding of culture as a rebellious power

The various scholars have quite a variety of different attitudes toward culture. As I have shown, Sanneh tends toward cultural relativism, while others insist on the possibility of comparing a culture to a baseline, whether it is Jesus as the original translation and the embodiment of all human diversity (Walls), or Jesus as Lord due to his having accepted to demonstrate and vanquish, from within a culturally particular vantage point, the power of culture to keep people apart (Yoder). Yoder has the most coherent account of what exactly about culture is rebellious: culture as a structure or power rebels against its God-given mandate by working to keep human beings apart, by reinforcing enmities and rivalries.92

While I agree that it is necessary to emphasize the rebellious nature of culture, this statement needs to be qualified so that it does not lead to an anti-cultural message. The danger is that, while agreeing that we cannot escape particularity, we simply develop a new church culture that is unrelated to our former identities. Although I do not think Yoder is promoting this, his strong emphasis on the radical novelty of the new humanity can lead in this direction if we are not careful. Three clarifications are in order. First, we need a clearer account of what elements of culture might be morally neutral and thus not require critique. Yoder points in this direction when he suggests a differentiation between the evil, the finite or fallible, and the good that is “simply [cultural] ‘identity.’”93 Second, more reflection is needed regarding the question of whether cultures ever need to be the target of salvaging or revitalizing operations, in order to preserve human diversity for its own sake. Third, it is important to reiterate that culture should not be defined in a way that essentially conflates it with language. For example, in the case of Burkina Faso mentioned earlier, discourses that equate language with cultural identity can delegitimize local church leaders’ concerns about the risks of developing ethnically homogenous churches.94 Finally, it is essential not to define the new humanity in a way that glosses over power differences related to cultural identity. There needs to be space for lower-power groups to work out what it means to live in a truly reconciled way with former enemies in cases of structural cultural conflict, without using the idea of the “new humanity” as a whitewash for ongoing inequality. While Yoder’s work points us in this direction in theory, awareness of the stark abuses of power in his own life will lead us to also look elsewhere for ideas.

As long as it is properly qualified in these ways, I believe that a view of culture as a rebellious but redeemable power is necessary, both in order to avoid the trap of cultural relativism and to prevent cultural or national identity from ever taking the place of the primary allegiance to the new humanity. The particular strength of both Walls’ and Yoder’s accounts is their understanding of the new humanity as the true, redeemed form of culture. Walls goes furthest in exploring the New Testament metaphors for this new humanity as a body, a city or a temple. However, to correct for his tendency to abstract away from the local congregation, we need Yoder’s emphasis on the way that the new humanity is lived out in concrete practices of truth-telling, conflict resolution, and sharing of meals. Also to compensate for Walls’ overly neutral view of culture, we need Yoder’s conception of the cross as a radical challenge to any cultural norms that would keep people from fellowship with one another.

Putting these pieces together, we arrive at the idea that the new humanity does not abstract away from culture but is a foretaste of what culture is ultimately meant to be. The diversity of the church is necessary to demonstrate Christ’s fullness, but the overcoming of culture’s rebelliousness by subjecting it to Christ’s lordship (especially overcoming culture’s tendency to divide people) is how it is truly redeemed. In short, I believe it is true to insist that the only “real” culture is the culture of the Kingdom of God. In this Kingdom, every culture that God has created is able to bring its best to the table (Walls); yet no rebellious aspect of culture remains that would prevent fellowship across cultural lines (Yoder). This is a global body that learns to value the contributions and new perspectives brought by others; but it is also local bodies working diligently to overcome the social barriers in their midst, even when this means that their members sometimes give up time to focus on the conversion of their own cultures so that they can learn a new thing about Christ from the perspective of other brothers and sisters.

Relevant social grouping

The various authors envision their account of plurality in the church as being relevant to quite a variety of different types of social bodies. Sanneh leaves a strong impression that translatability has the greatest effect, not on the church per se, but on indigenous cultural groupings. Walls tends to abstract away from the local church in order to rhapsodize about the global body; it might be this abstraction that makes it possible for him to open the door to considerations of a Christian nation whose boundaries may or may not coincide with that of the church. Those who share a culture become the most relevant social grouping to which the translatability imperative is addressed. Finally, Yoder’s insistence that the church is both the message and the medium means that, for him, particular Christian communities with specific social practices are of paramount importance.

A comparison of the different positions leads me to conclude that the social grouping to which the challenge of translation is addressed can only meaningfully be the new humanity. However, this social grouping is not just made up of various cultural building blocks; it is itself, in some way, a culture. If the faithful church is sociologically specified in ways that derive from Jesus, then the gospel itself requires a particular, redeemed cultural form in certain cases. Form is not ultimate, but within an Anabaptist ecclesiology it must play a greater role than simply that of a “casing” for a gospel essence, as per Walls’ analogy.95 If the most relevant social body is really the new humanity, then the gospel is not just the oxygen that breathes life into the habits and practices shared by one cultural group; it is a lifestyle shared by many groups whose culture has been redeemed.

The basis of translatability

We have seen that for Sanneh, translatability has no firm basis beyond the universality of God as transcendent above human culture, thus relativizing them all. Walls draws on the idea of the incarnation as an original translation against which subsequent translations need to be checked. He also touches on the concept of the new humanity, though it is grounded neither in the cross nor in specific local church practices, but in biblical images of the church that speak of Christ’s fullness being reflected through multiple cultural resources. Only Yoder develops the theme of the cross as a central part of his thought about the transmission of the gospel into different cultural forms.

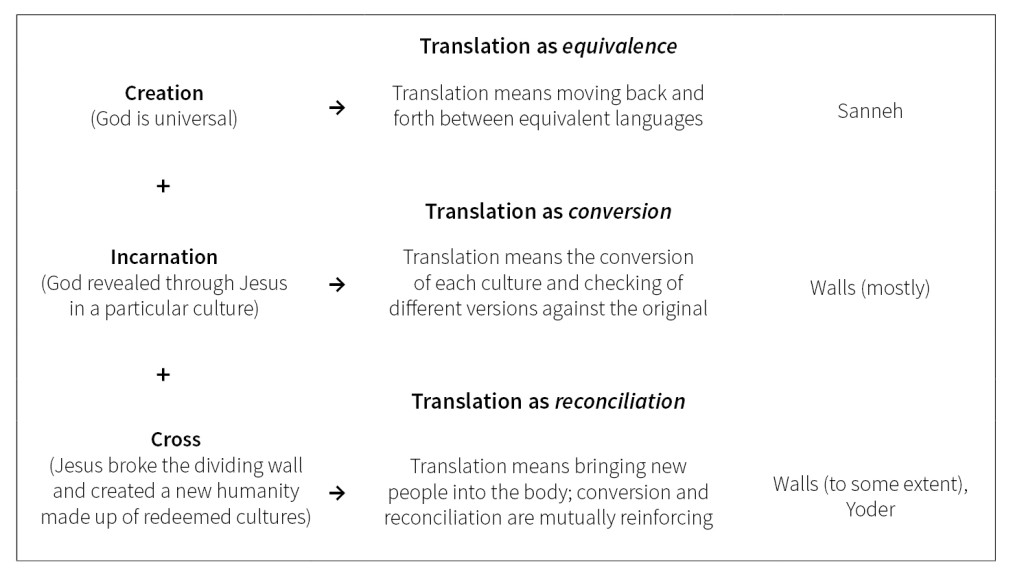

In order to respond to the challenges of the Ukarumpa, Québec, and Burkina Faso churches mentioned earlier, I believe we need an account of translatability that is firmly grounded not only in creation and in the incarnation, but also in the cross. Figure 1 expresses how, in my view, the three valid bases for translatability need to relate to each other in order to lead to a full account of what translation actually accomplishes.

As the plus signs show, the different versions build successively on the insights of previous versions, such that the creation or incarnation alone lead to incomplete views: translation seen only as equivalence or only as conversion will lead to distortion unless the reconciling element of the cross is also included.

The goal of translation

As the previous discussion has already implied, different accounts of translatability are animated by differing views as to the ultimate purpose served by translation. For example, the goal of translation may be to revitalize a culture (Sanneh), to build the church into the full-grown humanity through which Christ can be fully displayed (Walls) or to bring worldviews into submission to Christ’s lordship through their integration into the new humanity (Yoder). I propose that we understand the purpose of translation within the larger perspective of the mission of the church. The church’s ultimate goal is to attain to the full stature of the body of Christ that includes the converted versions of every tribe, nation, people, and language. Within this ultimate goal, the purpose of the translation of the gospel is to help bring new groups in to the existing body. The purpose of translation can never be to create an isolated church that somehow reflects Christ really well on its own, because what is most fundamental about Christ is not being reflected if reconciliation is not happening across cultural boundaries.

The tension between the universal and the particular

I will finish this discussion by relating it to one of the points with which I began: the question of translatability is relevant to the contemporary discussions about cultural relativism and to the tension between the universal and the particular. The different accounts are not all equally successful at addressing this tension. Translatability indeed relativizes culture by showing that none is absolute, as Sanneh says, but that is not enough. We need to be able to critique culture in terms of faithfulness and sinfulness, as Yoder rightly points out. This requires Walls’ notion of an original version that qualifies the subsequent versions. The fact that this original is still culturally specific because of the incarnation allows us to reject relativism to some extent, since God’s universal truth is expressed through irreducible particularity. Translatability then affirms that because this truth is expressed in one particular culture, it can be expressed in any other cultural terms as well.

However, while this approach guards against relativism to a degree, I believe that Yoder’s account allows us to go even further. The new humanity is the place where the tension between universal and particular can be fully addressed. This is because the new humanity is made up of particular cultures redeemed through submission to Christ’s universal lordship, and because this lordship was attained not only through the embrace of a particular identity, but also through the demonstration at the cross that the rebelliousness of that identity could be vanquished. In fact, the new humanity might be the only place where cultural diversity can be welcomed without succumbing to cultural relativism, because this is the only place where culture is truly redeemed.

Conclusion

I have attempted to make three contributions to the debates about translatability, the worldwide church, and the challenge of pluralism or relativism. First, I have shown that different scholars use the concept of translatability in very different ways. Translatability can be associated with radically divergent underlying ideas about the nature of culture, the most relevant social grouping, the theological basis of translatability, its ultimate purpose or goal, and its ability to address the tension between the universal and the particular. In other words, “translatability” as a Christian doctrine cannot be translated that easily from one scholar to the next.

Second, I have attempted to show that the translatability and pluralism debates can be brought together fruitfully. The pitfalls of pluralism that philosophers point out are also relevant inside the translatability debate, where cultural relativism remains a tempting perspective. The discourse about translatability is relevant to the tension between cultural pluralism and Jesus’ unique truth-claims, with the tension between the universal and the particular being resolved in the new humanity. Thus the translatability concept helps to clarify the challenges of pluralism, and vice versa.

Third, I have engaged with each of the five dimensions of translatability mentioned earlier in order to move closer to a theologically robust account. I suggested that translatability takes on its true meaning and purpose within the context of the new humanity brought into being at the cross. Only the cross provides a perspective within which translatability can be understood as integrating people(s) or “culture-specific segments” into the global church, and only in the new humanity is the tension between the destigmatization and relativization of culture satisfactorily addressed. While the incarnation destigmatizes cultural particularity, culture must be recognized as rebellious through its tendency to divide and exclude people. Through Jesus’ willingness both to embrace cultural particularity and to overcome sinful human divisions at the cross, the new humanity is created as a historical, timeful, and particular people who by its concrete practices experiences a redeemed way of being human that is a foretaste of the full stature of the universal Christ. Translation can be understood as a mutually reinforcing process in which the conversion of our culture leads to reconciliation between cultures, and in which reconciliation between cultures leads to the conversion of each one.

The implications of such an account are multiple. I conclude with several practical suggestions to help us navigate the challenges of living out this new humanity in our local congregations.

First, we must expect conflict as we negotiate the cross-cultural differences in our congregations; coming up with practical tools to resolve our conflict should be a priority, and we should not be surprised if the New Testament offers us several such tools on a close reading. David and Cynthia Strong’s analysis of the Jerusalem Council suggests that a community hermeneutic can be a useful tool for cross-cultural decision-making and unity inside a multicultural church.96 The sacramental practice of reconciling dialogue97 can be carefully adapted to different cultural contexts to help us resolve interpersonal conflict. While we can affirm that some might have a special gift of cross-cultural expertise,98 all are called to the hard work of conflict resolution across social boundaries, and all should be pursuing “cross-cultural competence.”99

Second, if there is an older Christian community, mostly monocultural, that “has the law,”100 it should make the more significant concessions when welcoming members from other cultures. Just as Paul did not want Galatian Gentiles to be circumcised, the prior members of a congregation should not impose their alienating cultural forms on new members.

Third, everyone’s culture reveals Christ in a different way and has a part to play in the body or temple or new humanity. The potential of everyone’s culture should be affirmed, but cultural sensitivity or political correctness should not prevent us from challenging cultural forms that from our perspective are rebellious. However, this hard work of challenging each other’s cultures needs to occur while sharing in congregational life; it cannot happen if we are not also worshiping together, eating together, and making decisions together.

Fourth, in contrast to Paul’s strategy, the modern missionary movement has involved planting churches from scratch rather than starting with a “synagogue.”101 Even if we see this as a mistake, we must find a way to respond to this unique situation. Perhaps it is time for a new push to develop gospel-sharing methods that focus primarily on the creation of truly intercultural communities around the world: communities that embody the good news in ways that profoundly call into question old ways of relating between expatriate missionaries, sending churches, and believers in the host country.

Fifth, the challenge of intercultural existence brings us face to face with the grave disparities in power and wealth that undermine the unity of the world church. Many approaches exist to try to balance power in the worldwide church, including Ron Sider’s plea for rich North American Christians to give far more to the poor,102 and Jonathan Bonk’s exposition of the way that riches prevent authentic relationships and undermine ministry for expatriate missionaries.103 Some approaches have a particular focus on re-establishing relationship by emphasizing inter-congregational connections and global gift-sharing.104 As essential as all these contributions are, there is a great need to build more firmly on a foundation of intercultural existence at a local level, where social boundaries are being scandalously disrupted every day. This would rest on the starting point that “people are crucified for living out a love that disrupts the social order, that calls forth a new world. People are not crucified for helping the poor. People are crucified for joining them.”105

Sixth, we can continue the conversion of our own rebellious culture by evaluating our existing church practices to see how well they contribute to the constitution of the new humanity. For example, Metzger calls for caution about the tendency for North American evangelical and emerging churches to be built on homogenous small groups.106 Cavanaugh brings wisdom about how the Eucharist can help us to address particularity with a non-consumerist mindset. Instead of treating our differences as something to be consumed,107 thus draining the “particular…of its eternal significance,”108 we become “more universal, the more [we are] tied to a particular community of Christians gathered around the altar.”109

Finally, the work of living out the new humanity will require special attention to music and language. Music is an element of culture that is bounded and yet to some extent accessible across cultural boundaries; language on the other hand can only be understood and appreciated by those who speak it. How can we develop ways of relating in intercultural churches that take into account the imperative both of doing church together, and of affirming the value of particular musical and linguistic traditions? More work is needed to develop a balance between incorporating musical traditions of those who are far away as an expression of solidarity with the worldwide church,110 and working with multiple traditions that are all represented by local church members. Much more work is needed to develop similar principles of intercultural worship when it comes to language choice in church services.

To conclude, we dare not abstract away from the concrete work of being intercultural congregations who work together on transcending the cultural and social barriers that divide us, while continuing to honour the particularity of each other’s cultures. In our churches, whether in Ukarumpa, Burkina Faso, Québec, or elsewhere, we participate in the conversion of our cultures and the reconciliation with others as we eat together in defiance of social divisions, resolve our conflicts through reconciling dialogue, welcome diverse cultural elements into our worship, and include those of different backgrounds in making decisions together.

Footnotes

Anicka Fast holds an MA in Language Documentation and Description and hopes to begin a doctorate in theology in 2015. She is a member of the Centre d’Études Anabaptistes de Montréal (Montréal Centre for Anabaptist Studies) and is actively involved in the leadership team of her local church. She is married to John and has two daughters. Thanks to Glenn Smith and Marianne and Lesley Fast for comments on an earlier version of this article.

Anicka Fast, “Managing Linguistic Diversity in the Church,” in Language Documentation and Description 6, ed. Peter K. Austin (London: SOAS, 2009), 161–212.

Having recently become more aware of the extent of Yoder’s wide-ranging and long-term sexually abusive behaviour, I am painfully conscious that it is insufficient to simply note Yoder’s transgressions and then proceed to use his work as though it is divorced from his life. I welcome the discussions that are developing in which Yoder’s work is being reanalyzed in order to probe which specific theological claims may need to be revised to take into account blind spots deriving from his abuse of power, or even dismissed in light of his behaviour (for one important contribution, see Hannah Heinzekehr’s August 9, 2013 post on the femonite blog [www.thefemonite.com], entitled “Can Subordination Ever Be Revolutionary? Reflections on John Howard Yoder”). Yoder’s work on intercultural reconciliation in the church resonates deeply with me. At the same time, I am attempting to consider how his ideas on this subject might be flawed. While I comment on one specific example later in the paper, I welcome suggestions from others about what I might have missed. I believe the process of working through and reevaluating Yoder’s work in light of his personal legacy will take time, but that it is a worthwhile and necessary endeavor.

Lamin Sanneh, Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1989), 4.

Ibid., 2, 7, 206–7.

Ibid., Translating the Message, 1.

Ibid., 34.

Lamin O. Sanneh, Disciples of All Nations: Pillars of World Christianity (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 161.

Sanneh, Translating the Message, 24.

Ibid., 15.

Ibid., 25.

Sanneh, Disciples of All Nations, 6.

Sanneh, Translating the Message, 206.

Ibid., 207.

Ibid., 5.

Sanneh, Disciples of All Nations, 27 (emphasis added).

Sanneh, Translating the Message, 25.

Ibid.

Ibid., 47.

Ibid., 2.

Sanneh, Disciples of all Nations, 25.

Sanneh, Translating the Message, 2.

Fast, “Managing Linguistic Diversity,” 202–3.

Andrew F. Walls, The Missionary Movement in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission of Faith (Maryknoll: Orbis, 1996), 26–27.

Ibid., 47, emphasis original.

Ibid., 27.

Ibid., 49–51.

Ibid., 53.

Ibid., 28.

Ibid., 27–28.

Ibid., 30, 54.

Ibid., 54.

Andrew Walls, “The Ephesians Moment in Worldwide Worship: A Meditation on Revelation 21 and Ephesians 2,” in Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices, ed. Charles E. Farhadian (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 32.

Ibid., 27.

Ibid., 31.

Ibid.

Andrew F. Walls, The Cross-Cultural Process in Christian History: Studies in the Transmission and Appropriation of Faith (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2002), 77.

Walls, Missionary Movement, 51.

Walls, Cross-Cultural Process, 81.

Ibid., 79.

Ibid., 78.

Ibid.

Walls, Missionary Movement, 40.

Walls, “Ephesians Moment,” 37.

Walls, Missionary Movement, 54.

Walls, Cross-Cultural Process, 48.

Ibid., 78.

Ibid., 77.

Walls, Cross-Cultural Process, 77; and Walls, “Ephesians Moment,” 30.

John Howard Yoder, For the Nations: Essays Evangelical and Public (Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 1997), 63.

Andrew Scott Brubacher Kaethler, “The Unruliness of Language: Language, Methodology and Epistemology in the Thought of John Howard Yoder” (doctoral dissertation, Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, 2013), 299. Kaethler’s exposition of Yoder’s theology of language is based mostly on an unpublished lecture to which I did not have direct access.

John Howard Yoder, Body Politics: Five Practices of the Christian Community before the Watching World (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1992), 39.

John Howard Yoder, “The Homogenous Unit Principle in Ethical Perspective” (unpublished essay prepared for the Fuller Seminary Pasadena Consultation in May 1977), 10. Accessed March 11, 2014, http://replica.palni.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/p15705coll18/id/306/rec/1.

Ibid., 11.

John Howard Yoder, “‘But We Do See Jesus’: The Particularity of the Incarnation and the Universality of Truth,” The Priestly Kingdom: Social Ethics as Gospel (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1984), 56.

John Howard Yoder, Theology of Mission: A Believers Church Perspective (Downers Grove: IVP Academic, 2014), 315.

Yoder, “But We Do See Jesus,” 49.

Ibid., 62.

Ibid., 49.

Ibid., 54.

Ibid.

Ibid., 61.

John Howard Yoder, “Peace without Eschatology?” in The Royal Priesthood: Essays Ecclesiastical and Ecumenical, ed. Michael G. Cartwright (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1998), 164.

Ibid.

Yoder, Theology of Mission, 310.

John Howard Yoder, The Politics of Jesus: Vicit Agnus Noster (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1972), 242

Yoder, “Peace without Eschatology?” 149.

Yoder, Body Politics, 28; and Yoder, Theology of Mission, 100.

Yoder, Body Politics, 30.

Ibid., 35.

Ibid., 37.

Ibid., 38.

Yoder, For the Nations, 41 (emphasis original).

Yoder, “Homogeneous Unit Principle,” 14–15.

Yoder, Theology of Mission, 215.

Yoder, Body Politics, 78.

Ibid.

Ibid., 46.

Ibid., 18

See the discussion of other similar cases in Yoder, Theology of Mission, 213–27.

Yoder, “Homogeneous Unit Principle,” 13.

Ibid., 11.

Yoder, Body Politics, 37.

Yoder, Theology of Mission, 105.

Ibid.

Yoder, “Homogeneous Unit Principle,” 15.

John Howard Yoder, As You Go: The Old Mission in a New Day (Scottdale: Herald Press, 1961).

Yoder, “Homogeneous Unit Principle,” 16.

Yoder, Theology of Mission, 75–128.

Yoder, “Homogeneous Unit Principle,” 16. See also the discussion in Yoder, Theology of Mission, 97.

Yoder, Theology of Mission, 315.

Yoder, Body Politics, 39.

Yoder, “Homogeneous Unit Principle,” 10.

Fast, “Managing Linguistic Diversity,” 204–5.

Walls, “Ephesians Moment,” 32.

David K. Strong and Cynthia A. Strong, “The Globalizing Hermeneutic of the Jerusalem Council,” in Globalizing Theology: Belief and Practice in an Era of World Christianity, eds. Craig Ott and Harold A. Netland (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 134.

Yoder, Body Politics.

Paul G. Hiebert, “The Missionary as Mediator of Global Theologizing,” in Globalizing Theology: Belief and Practice in an Era of World Christianity, eds. Craig Ott and Harold A. Netland (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2006), 288–308; Yoder, For the Nations, 73.

Sam Owusu, “‘To All Nations’: The Distinctive Witness of the Intercultural Church,” in Green Shoots out of Dry Ground: Growing a New Future for the Church in Canada, ed. John P. Bowen (Eugene: Wipf & Stock, 2013), 124.

Yoder, “Homogeneous Unit Principle,” 14.

Ibid., 15.

Ron Sider, Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger: Moving from Affluence to Generosity (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2005).

Jonathan Bonk, Missions and Money: Affluence as a Missionary Problem…Revisited, revised and expanded edition (Maryknoll: Orbis, 2006).

Pakisa Tshimika and Tim Lind, Sharing Gifts in the Global Family of Faith: One Church’s Experiment (Intercourse: Good Books, 2003); Alan Kreider and Eleanor Kreider, Worship and Mission after Christendom (Scottdale: Herald Press, 2011).

Shane Claiborne, The Irresistible Revolution: Living as an Ordinary Radical, large print ed. (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2006), 86.

Paul Louis Metzger, Consuming Jesus: Beyond Race and Class Divisions in a Consumer Church (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 62.

William T. Cavanaugh, Being Consumed: Economics and Christian Desire (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2008), 67.

Ibid., 71

Ibid., 85.

C. Michael Hawn, “Praying Globally—Pitfalls and Possibilities of Cross-cultural Liturgical Appropriation,” in Christian Worship Worldwide: Expanding Horizons, Deepening Practices, ed. Charles E. Farhadian (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 212.