Alan Kreider and Eleanor Kreider, in their work on Worship and Mission after Christendom, offer this insightful observation about the relationship of worship to mission for much of the history of Western Christianity:

During the Christendom centuries, the phrase “worship and mission” occurred rarely, if ever. Worship was what the church in Christendom existed to do; worship was its central activity. Mission, on the other hand, was peripheral and rarely discussed. Mission took place “out there,” in “regions beyond,” in “mission lands”—beyond Christendom.1

Not surprisingly, substantial differences in understandings of the relationship between worship and mission have continued to persist throughout the years. More often than not, the two are viewed as disparate aspects of the church’s faith and life. This perception has led to compartmentalization of worship and mission and, on occasion, provoked vigorous discussion about the role of each. Current approaches to this debate can be summarized by three emerging views:

- Traditional view. The first and more conventional approach affirms an understanding wherein believers are “gathered” for the edification of the body in order to be “sent out” into the world as disciples in God’s reconciling mission.

- Contemporary view. The second view focuses primarily on nonbelievers via “seeker services,” wherein worship content is adapted to appeal to the unchurched. The worship service is thus primarily considered a platform for evangelization.

- Integrated view. With either of the two previous views, however, unanswered questions remain. Is it not artificial, for example, to separate worship and mission in this manner? Can the church not cultivate a more integrated approach that bridges the gap between the two? Might there be a third way of understanding mission and worship that would enhance and unify the church’s worship and its missional purpose?2

Mennonite missiologist John Driver has argued that this latter, integrated approach is more in tune with Anabaptist theological commitments. In his view, what interested these radical reformers was “the prospect of ‘walking in newness of life,’ thanks to a regeneration experienced through the marvelous grace of God that expressed itself in the integration of faith and works, of the individual and the community, and of service and witness.”3

The following essay is our modest attempt to join this important conversation. We will begin by examining worship components and mission commitments present in the wide variety of early sixteenth-century Anabaptists in continental Europe. From there, we will explore the interrelatedness of worship, culture, and mission in contextualized Majority World Anabaptist/Mennonite communities around the globe today. To conclude, we will highlight some reflections from a handful of newer Anabaptist voices and the manner in which they are integrating and contextualizing the faith in their life settings and places of ministry.

Looking Back: Worship Components and Mission Commitments in Early Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism

From the very beginning, God’s people were called out and sent forth as a missional people (Gen 12:1–3). This is at the heart of the church’s identity and is the very soil out of which the church was birthed. The Anabaptist genius in the early sixteenth century, according to Wilbert Shenk, “was to recognize that the Christendom concept of the church was at odds with the apostolic vision.”4 Jesus’s final commission to his disciples, in Anabaptist understanding, defined the church’s permanent responsibility to the world and called for concrete

action. Thus, baptism was meant for adults, writes Shenk, “because it involved an unconditional commitment to discipleship expressed in witness to the gospel in all circumstances.”5

Likewise, worship was a fundamental part of Anabaptist life. Its essence was rooted in the work and teachings of Jesus and in discipleship that resulted from a commitment to “observe all things” as Jesus had commanded (Mt 28:20).6 Worship for Anabaptists involved a tri-dimensional dialogue of the collective assembly: to come together for the interconnected purposes of (1) praising and adoring the triune God, (2) mutual edification of its members, and (3) strengthening its two-directional commitment and practice of mission in both inward and outward motions.

With rumblings of the Mosaic Covenant and the New Covenant in Christ as foundational backdrops, worship and mission were creatively and integrally intertwined in the thought and practice of early Anabaptism. The movement itself was, in fact, initiated through a missional act of worship—the community practice of adult baptism—which included, as John Driver has pointed out, a commission directed to the baptismal candidate “to participate in God’s saving mission in the world.”7 This combined commitment to both “missional worship” and “worshipful mission”8 expressed itself in Anabaptist worship praxis, prayers, sermons, and hymn texts as well as in the members’ passionate obedience to Jesus’s final words of commission to make disciples by “teaching all things” and by baptizing.9 The Anabaptists’ submission to both of these activities became key elements of their “practical theology” of integrating worship components with mission commitments.

With regard to the specific worship patterns and practices of early Anabaptists, we should note that in reaction to the lavish pomp and pageantry of the state-sponsored church worship services of their day, Anabaptists wished to return to simpler patterns observed by the early church. At least one Anabaptist leader, Conrad Grebel, reportedly agreed with Swiss Reformer Ulrich Zwingli that all church music, including singing, should be eliminated from corporate worship services.10 Yet, despite these rather harsh views, early accounts by the 1560s record at least 130 Anabaptist hymn composers by name, indicating that “the singing and reading of hymns was practiced both in congregational worship services and in private and personal devotions.”11 Of additional significant note in the 1562 Dutch Anabaptist collection of hymns, the Lietboecxken van den Offer des Heeren, is the large number of women hymn composers.12 This collection, along with the contemporaneous publication of the Ausbund hymnbook, provided continental Anabaptists with ways and means of singing their theology in worship settings as well as in the marketplace and from their prison cells as a form of public witness.13

One particularly insightful description of early Anabaptist worship patterns suggests that “when Anabaptists came together, they read the Bible, prayed, chose leaders, exhorted one another to be faithful in persecution, broke bread together, baptized, and debated with non-members in their midst”14—all acts of worship, we might note, that are fundamentally connected in the Anabaptist perspective to the Great Commission. In accordance with their commitment to simplify worship rituals, “sacred hours, vessels, or places were not elevated above the rest of life because all of life was sacred.”15 Consequently, Anabaptists “felt no need to set aside a special time or place for this activity. Thus, they met at different times and places throughout the week when led by the Spirit.”16

Anabaptists’ deep passion for openly sharing their faith was the starting point for their understanding of the church to which all members were bound as a kind of “lay apostolate.”17 One person who exemplified this kind of simple gospel communication was Peter Ehrenpreis of Urbach, who in 1596 is said to have won the favor of his neighbors, drawing them to his way of living “with his Anabaptist songs which he is accustomed to sing in his vineyard and elsewhere.”18

According to Paul Wohlgemuth, Anabaptist hymnody used four primary sources of tunes: Roman Catholic liturgy, German Protestant hymn tunes, pre-Reformation German sacred folk songs, and secular folk tunes. Most akin to Anabaptist hymns were the sixteenth-century grassroots and culturally popular German Volksliederen—folk songs—known for expressing emotions of sorrow, love, and loneliness while describing daily life, national events, and heroes to local celebrations, parties, and festivals.19 “It is not strange, then,” notes Rosella Reimer Duerksen, “that members of the Anabaptist group should express their experiences, as well as their innermost feelings, through the medium of the Volkslied, and it is consequently this genre, with its acknowledged debt to the product of the Meistersinger, that one must consider the immediate soil from which the Anabaptist hymn sprang and by which it was nurtured.”20

Not surprisingly, early Anabaptists’ mission fervor and the harsh persecution that followed significantly shaped the movement’s worship practices and prevented the emergence of a well-regulated congregational life. Much worship in the early days took place at night in the forest, on remote farms, in isolated mills, or sheltered in huge rock caves, far from authorities—and in hushed tones to avoid being detected. Mennonite historian Christian Neff writes:

A flood of religious songs poured over the young brotherhood like a vivifying and refreshing stream. The songs became the strongest attractive force for the brotherhood. They sang themselves into the hearts of many, clothed in popular tune. They were mostly martyr songs, which breathed an atmosphere of readiness to die and a touching depth of faith.21

Some worship gatherings served as commissioning services for out-going missionaries, in which candidates gave testimony to their calling and received prayer, counsel, and encouragement for the dangers ahead. One remarkable twenty-five-stanza hymn used in an early commissioning service recognizes the realistic possibility that those being sent forth might well “taste sword and fire” and never return:

And if thou, Lord, desire

And should it be thy will

That we taste sword and fire

By those who thus would kill

Then comfort, pray, our loved ones

And tell them, we’ve endured

And we shall see them yonder—

Eternally secured.22

Nearly five hundred years subsequent to these dramatic sixteenth-century events, Anabaptists from across the globe gathered in Canada in the summer of 1990 in Winnipeg, Manitoba, for the twelfth Mennonite World Conference (MWC) assembly.23 A book of songs compiled as a resource for the worship services at that gathering included a piece titled “We Are People of God’s Peace,” taken from previous MWC songbooks. It was written by David Augsburger and adapted by Esther Bergen. The text of this song was a versified translation of the writings of Dutch Anabaptist church leader and movement founder, Menno Simons (1496–1561), based on some of his favorite biblical texts—Romans 14:19, 2 Corinthians 5:17–19, and Ephesians 2:14–18.24 The hymn text declares:

We are people of God’s peace as a new creation.

Love unites and strengthens us at this celebration.

Sons and daughters of the Lord, serving one another,

A new covenant of peace binds us all together.We are heralds of God’s peace for the new creation;

And by grace the word of peace reaches ev’ry nation.

Though we falter and we fail, Christ will still renew us.

By the Holy Spirit’s pow’r, God is working through us.We are children of God’s peace in this new creation,

Spreading joy and happiness, through God’s great salvation.

Hope we bring in spirit meek, in our daily living.

Peace with ev’ryone we seek, good for evil giving.We are servants of God’s peace, of the new creation.

Choosing peace, we faithfully serve with heart’s devotion.

Jesus Christ, the Prince of peace, confidence will give us.

Christ the Lord is our defense; Christ will never leave us.

This hymn brings together a number of themes important to sixteenth-century Anabaptists and to the one and a half million global members of the MWC body today.25 In these four stanzas, Anabaptists clearly identify themselves as participants in God’s reconciling mission in the world, “spreading joy and happiness, through God’s great salvation.” They are “heralds of God’s peace” for the new creation that God is bringing about. Achieving God’s purposes will not happen by the mighty forces of human effort. Rather, it is by God’s grace that “the word of peace reaches ev’ry nation.” Despite human faltering and failing, “Christ will still renew us.” For “by the Holy Spirit’s pow’r, God is working through us.”

The communal sense of belonging to God’s people is a deep value for Anabaptists. We are heralds. We are servants. We are children. We are people of God’s peace. God has called forth a people to be the primary model and messenger of a cosmic project to reconcile all things in Christ (Col 1:20), recruiting and naming members of this people as nothing less than “ministers of reconciliation” and “ambassadors of Christ” (2 Cor 5:18, 20).

If reconciliation is the message of God’s project, it is also its method of delivery, characterized—as the song text affirms—by faithful service, meekness of spirit, devoted hearts, lives of peace, generosity toward evildoers, and confidence in Christ’s abiding presence at all times and in all places. Such were the desired characteristics of early Anabaptists—many of them simple folk with limited education, “sons and daughters of the Lord” bringing hope in daily living and “serving one another” in “a new covenant of peace” that “binds us all together.”26

Harold S. Bender confirms this view in citing nineteenth-century German historian Rochus Liliencron on Anabaptist hymn texts:

Love is the great and inexhaustible theme of [Anabaptist] hymnody; for love is the sole distinguishing mark of the children of God. . . . For the brethren, love is the “chief sum” of their being. . . . So, these hymns immerse themselves in the concept of the love which is all in all, which takes up its cross with joy, which gives everything in the service of God and the neighbor, which bears all things, and out of which flows all humility and meekness, mercy, and peace.27

Looking Forward: Worship and Mission Practices and Challenges for Twenty-First Century Anabaptists

One of the identifying signs of Anabaptist faith communities is reflected in the life together of a reconciled and unified body of worshipers gathered around and sent forth by The Reconciler, God incarnate in Jesus Christ.28 As referenced earlier, worship and mission are thus integrally related and inseparable components in God’s project of the redemption of all creation.

- T. Wright points out, “The key to mission is always worship. You can only be reflecting the love of God into the world if you are worshipping the true God who creates the world out of overflowing self-giving love. The more you look at that God and celebrate that love, the more you have to be reflecting that overflowing self-giving love into the world.”29

Worship encompasses and joins together redemption in and through Christ in the power of the Holy Spirit. Facets of this worship include peace and justice; the enactment of reconciliation with God and one another through confession, forgiveness, baptism; and communion, unity in diversity, harmony, and community.

The gospel in all its full-orbed richness must be announced (kerygma), lived (koinonia), and shown (diakonia). These three aspects are united in mission.30 In this interplay, corporate worship—via the Holy Spirit—forms and transforms us to do God’s purposes in our personal lives, in the church, and in the world.

When worship and mission are reconceived in this way, mission takes its place at the center of worship, and God’s people are reminded—in the words of Kreider and Kreider—that “when our worship glorifies God, it does so by praising God for God’s actions and attuning us to God’s missional purposes. When God through our worship sanctifies us, God conforms us to God’s missional character and empowers us to participate in the missio Dei.”31 In this inner and outer synthesis of worship and mission, God’s reconciling project becomes an integrated whole in the understanding of the life and nature of the church.

In this way, writes Mark Labberton, “worship sets us free from ourselves to be free for God and God’s purposes in the world. The dangerous act of worshipping God in Jesus Christ necessarily draws us into the heart of God and sends us out to embody it, especially toward the poor, the forgotten and the oppressed.”32 God’s mission forms the church’s worship. And worship, in turn, motivates and empowers the church for God’s mission.

Culture Interacts with Worship and Mission in Four Principal Ways

As newly forming Anabaptist communities are born and shaped in diverse sociocultural contexts around the world, they will encounter significantly different challenges than did their sixteenth-century spiritual ancestors. Will Euro-North American Anabaptists be able to muster the humility, patience, and creativity necessary to walk alongside them on this journey? That is yet to be seen.

In the meantime, perhaps some insights from the Lutheran-generated “Nairobi Statement on Worship and Culture”33 can facilitate this effort. The statement highlights four fundamental principles that can and should relate dynamically to all settings worldwide—including Anabaptist ones—in the understanding that faithful worship and accompanying missional activity are to be (1) transcultural, (2) contextual, (3) countercultural, and (4) cross-cultural. Adapted to Anabaptist communities, this might mean the following:

Transcultural. The church is a worldwide family. Regardless of the culture, the basic gospel content remains the same for everyone everywhere. There is unity in our diversity because of the person and work of Jesus Christ, who is the central driving force of our faith, life, and witness of the church. We read the same Scripture and celebrate baptism and the Lord’s Supper in an Anabaptist perspective. We believe the church is service oriented and missional inside and outside.

Contextual. The characteristics of the cultural context, specific questions, language, biblical insights, gestures, song, and dress are valued and reflected in each church’s worship patterns and ways of sharing the good news in the world. The Word needs to “become flesh” in each and every culture and context.

Counter-Cultural. While each cultural context reflects the beauty of God’s creation, it also has its sinful, selfish, greedy, warmongering false gods that clash with and compromise faithful gospel truths and practices. Even as it affirms the positive aspects of culture, missional worship also names and denounces the multi-layered dynamics of all idols in any given culture that do not conform to the values and purposes of God’s reign. It further teaches believers how to resist them in ways that reflect Jesus’s life and teachings and equips them to share with others God’s desire to redeem and transform the world.

Cross-Cultural. The celebration of Creation and Pentecost reminds us of the richness of unity in diversity. Our church life reflects this richness when we incorporate in our worship experiences songs, prayers, and arts from faith communities in other cultures within our own neighborhoods and from across the Anabaptist and broader Christian family worldwide. Such practices help break down the cultural walls and ethnocentrism that often separate us. More importantly, they point us to the missional future that God is preparing—when people of every tribe, tongue, and nation will gather in worship around the throne of God and of the Lamb (Rev 7:9).

One current attempt to contextualize worship and mission principles in an Anabaptist perspective can be found in the Châtenay Mennonite Church in the urban setting of Paris, France. There, people from many nations and cultures are seeking to give a positive, visible witness to the gospel message and the nature of Christ’s church as a multicultural body. This congregation’s life—though far from perfect—can serve as an example of how worship and mission in a post-Christendom context can be part of the same large reality of the missio Dei.

The Châtenay faith community began in the early 1950s with five people meeting in a bus parked in a working-class suburb on the outskirts of Paris. At its origins, the congregation was almost exclusively white and middle class. Its members were primarily local Christians of various denominational backgrounds and people from families that had been Mennonite for many generations in Eastern France, who had moved to the capital city for jobs.

As migration from the Global South increased over the years and the demographics of the neighborhood shifted, so too did the “face” of the faith community. With an influx of African, Haitian, and other immigrants, the church has transitioned into a multiracial, multicultural, and multigenerational urban congregation. Such change has meant that the congregation must develop concrete expressions of the gospel call to become a visibly unified and hospitable community amid great diversity in a highly secularized French context.

Small in its beginnings, the gathered group has grown into a thriving congregation. The desire for biblically based worship and unity in diversity are high priorities for its members. The very composition of the congregation and the multicultural nature of the surrounding neighborhood encourage members to become acutely aware of the importance of becoming a visible sign of God’s call to be a reconciled community where the walls of hostility—caused by differences in culture, language, color, gender, or age—are being broken down.

The ever-present challenge of the missional call remains how to visibly affirm and harmonize this biblical mandate in a common worship experience with believers of different Christian traditions and cultural backgrounds. How can one best learn that all have something to learn and understand from one another without forsaking beliefs, convictions, and missional worship practices in an Anabaptist perspective?

There are several ways in which Châtenay Mennonite Church attempts to take the necessary steps to achieve this purpose. The first and foundational one is holding in common a belief in God’s Story recounted in Scripture. The biblical account of God’s people is indispensable in defining the congregation’s identity and critical for an understanding of worship and mission, inside and outside. In this sense, missional worship and worshipful mission become one because The Story told in worship informs and transforms believers into missional disciples who flow into God’s missional project for the world. As Mennonite missiologist Wilbert Shenk says, “The missionary disciple must be thoroughly immersed in the missionary message and ministry of Jesus.”34 Scripture readings used as in-between words to introduce the different elements of worship enrich this mission of transformation.

Another way the congregation seeks to become an intentional and mutually inclusive missional worshipping community is through the conscious choice of church leadership and preachers who mirror the congregation’s heterogeneous group of believers. In turn, leaders from different cultural contexts deliberately cross frontiers in worship practices, enriching worship through use of intercultural and multilinguistic prayers and songs. In addition, active participation of all members is encouraged, according to their gifts and style, including both prepared and spontaneous participation.

In the spirit of Colossians 3:16, Ephesians 5:18b–20, Romans 14:19, and 1 Corinthians 14:15–26, the congregation’s singing constitutes an important element of worship. The musical plurality of the Châtenay congregation reflects the diversity of its members and gives broad expression of unity in a meaningful way. Efforts are made to encourage the inclusion of worship songs that reinforce the corporate and global nature of the church as a people of God as well as reflect the particular context and musical center of the congregation and its Anabaptist heritage.

These efforts are strengthened by intentional teaching on central biblical principles and key Anabaptist values of tri-dimensional worship—praising God, edifying the gathered community, and sending worshippers forth better equipped to participate in God’s reconciling work in the world.

The New Testament Frees the Global Church to Develop Missional Worship Patterns That Are Culturally Appropriate to Their Contexts

If global Anabaptist communities open themselves to worship and mission practices rooted within the cultural contexts where God has planted them, they will witness a flourishing of creative expressions that stay faithful to the central message of God’s reconciling work in Christ and, at the same time, will also build on the rich cultural gifts God has showered upon them in their specific local and national settings. We see such freedom and liberty being given to God’s people in increasing, incremental steps throughout the biblical story.

The Old Testament is packed full of very specific laws and requirements on virtually all aspects of life. With regard to worship, the text addresses worship spaces (the tabernacle and Temple), worship times and feasts (Sabbath and Passover), worship furnishings (bowls, incense, and the Ark of the Covenant), worship officiants (priests and Levites), worship rituals (water cleansings and sacrifices), worship garments (ephods, breastplates, and turbans), worship instruments (harps and cymbals), worship artists and composers (Bezalel, the sons of Asaph, and King David), and worship songs and liturgy (the Psalm collection and the public reading of the Law).

Mission itself was closely related to these worship patterns, for there was coming a day, proclaimed the prophet Micah, when peoples from all the surrounding nations would stream up to the Lord’s house in Jerusalem, learn of God’s ways, and sing Yahweh’s songs on Mount Zion (4:1–2). “Mission accomplished” for the Hebrew people would happen in worship, in the Temple, and in Jerusalem—the veritable center of Yahweh’s universe.

This all begins to change in the life, ministry, and “Great Commission” of Jesus, who sent his followers out of Jerusalem to the nations. “Mission accomplished” for the New Testament church would happen when groups of believers—as small in number as two or three—in every corner of the known world would gather in Jesus’s name and worship God “in spirit and in truth” (John 4:24).

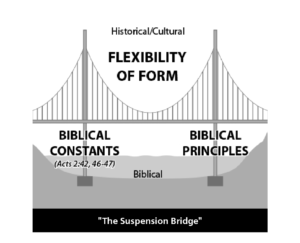

Now, there will necessarily be some biblical constants in this worship, as we see modeled in early church practice—proclamation of God’s Word, fellowship, prayer, praise, Christ-centeredness, the Lord’s Supper (Acts 2:42, 46–47)—as well as key biblical principles—God-focused, Christ-centered, Spirit-enabled, dialogical between worshippers and God, multi-voiced, participatory, and edifying both for individual worshippers and for the corporate body, equipping them for more effective participation in God’s mission. 35

Aside from these biblical constants and principles, the amazing freedom and flexibility that the New Testament grants to local communities of faith in developing their own forms and patterns of missional worship is nothing short of stunning. There appears to be little interest in the many objects and patterns of Old Testament worship, as if to encourage emerging congregations to find or create within their own widely dispersed and varied settings the worship places, times, dress, furnishings, and songs that build the local body of Christ in culturally appropriate, yet faithful ways. This dramatically transforms the missionary mandate of God’s people, reminding them never to lock the gospel treasure of new life in Jesus Christ in any particular cultural pattern but rather to encourage the creative work of the Holy Spirt in the lives and witness of local believers, in every time and place where the seeds of the good news are planted.

Worship and Witness through Various Stages in Mission History

“All worship is contextual,” write Mark Charles and Soong-Chan Rah, “but there may be an underlying assumption of European American primacy in worship and the failure to recognize the captivity of the church to European American norms.”36 There is no doubt that many Western missionaries carried with them this attitude of “primacy” and unawareness of their own cultural “captivity” to peoples and cultures they encountered around the world.

Because of this, many, if not most, Anabaptist faith communities have passed, or are currently passing, through a number of stages on their way to developing missional worship expressions and practices they consider truly “their own.” Such stages might include importation, adaptation, alteration, imitation, hybridization, exportation, and internationalization.

To be clear, these stages should not be thought of as some kind of chronological evolution—as a movie passing sequentially from frame to frame. Movement can and actually does pass in both directions—forward and backward—at any given moment. It is more helpful to consider these stages as photos—still-life snapshots capturing the missional worship patterns at a particular moment in time in the life of a congregation or denomination.

Certainly, not all churches will experience every one of the following stages, but these particular ones appear often enough to be helpful for our reflection here. If we apply these stages specifically to music development and implementation in the context of Majority World churches, we might make the following observations:

Importation—where song tunes, texts, and rhythms originate in Western-style music sources. For much of mission history, both past and present, the hymns of Watts, Wesley, Crosby, Gaither, or Hillsong Worship have simply been embraced and reproduced as accurately as possible by new believers in Majority World contexts. In some instances, local faith communities have come to genuinely cherish these musical styles and consider them as “their own.” Hymn tunes in particular are regularly featured in church services as well as at wakes, burials, and other situations where they offer solace and comfort. For other local believers, however, there persists a lingering, underlying sense of alienation, of “spiritual unsuitability,” with this imported musical legacy. The integrity of the church’s witness is likewise affected. Importing Western musical styles as the only ones employed by a Majority World faith community communicates to local “outsiders” that the religion itself is imported, “foreign,” thus creating an obstacle to the church’s mission. For these and other reasons, changes are often made to adapt or alter imported music to better fit the aesthetic sensibilities of the local context.

Adaptation—where imported song tunes, texts, or rhythms are in some way contextualized by rendering them more suitable or intelligible to worshippers in a given setting. In the adaptation process, nothing is substantially changed with imported songs. But an effort might be made to adapt tunes to the context of a particular faith community by introducing the use of locally produced instruments such as whistles, drums, rattles, or cowbells, for example. Or again, the decision might be made to translate song texts from a Western language into a locally spoken one. We should note here, however, that translated hymns—though perhaps more fully understood than those remaining in a “foreign” or imported language—are often little more than “shortcuts,” “temporary stopgaps,” and “from the point of view of their art, not the best.”37 One common predicament is that many words in local languages based on tonal patterns have their tones—and meanings!—altered when they are translated and sung to Western tunes.

Alteration—where some part of the imported song (tune, text, or rhythm) is replaced or otherwise significantly modified by an indigenous form. What happens in the alteration process is more than a simple “translation” of imported tunes (with whistles) or texts (with language) into a local idiom. Some part of the song receives a substantial alteration or total substitution of tunes, texts, or rhythms of indigenous composition or flavor. Examples of this more radical modification might include: (1) retaining imported tunes but writing new, local texts to replace the original ones;38 or (2) retaining original texts to put to new, locally composed tunes.39

Imitation—where tunes, texts, and rhythms are locally composed or performed but in a style that is inspired by, or replicates in some way, an imported musical genre. Ten years ago, Charlina Gozali, an Indonesian researcher,40 compiled the texts of over two hundred songs used regularly in churches known to her in Indonesia. The musical style was what one might generally classify as contemporary praise and worship, accompanied by guitars, drums, and keyboards rather than local indigenous musical instruments. Though familiar in sound to Western ears, over 80 percent of these songs were in fact composed by some sixty Indonesian songwriters who had produced worship music in an imported style they had learned to love. Similarly, from a West African ethnomusicologist,

Asante Darkwa, comes the observation that “nearly all the well-known

Ghanaian composers, as well as students, have tried to write hymn tunes.”41 One of the most famous of these composers was Dr. Ephraim Amu, an expert in Ghanaian indigenous music who also studied at London’s Royal School of Music from 1937 to 1940. He eventually composed and published a collection of forty-five choral works.42 Illustrations abound throughout the Majority World of musicians who have composed songs for worship in the styles of nineteenth-century revivalist hymns; southern gospel; four-part male quartet arrangements; and, increasingly on the contemporary music scene, in the popular genres of country and western, hip-hop, reggae, and rap.

Indigenization—where tunes, texts, and rhythms are locally produced in indigenous musical forms and styles. Many first-generation Christians around the world have either been taught or have chosen to resist using indigenous tunes, languages, and instruments in worship because of the emotional and spiritual associations these tend to conjure up from their former lives. What is also true, however, is that nothing inspires more and brings to life much of the church in Africa, Asia, and Latin America than singing and dancing the indigenous “heart music” of their respective cultures. Whenever such music is introduced into local worship experiences, something almost magical immediately sets in. “At once,” observes E. Bolaji Idowu, “every face lights up; there is an unmistakable feeling as of thirsty desert travelers who reach an oasis. Anyone watching . . . will know immediately that [the] worshipers are at home, singing heart and soul.”43

Indigenous, locally composed music does not need to be the only diet for the church. But a healthy church will produce and encourage such music as a central goal, nonetheless; for “when a people develops its own hymns with both vernacular words and music, it is good evidence that Christianity has truly taken root.”44

Hybridization—where the tunes, texts, and/or rhythms of a particular musical style or genre are blended with the tunes, texts, and/or rhythms of other musical styles or genres to produce a new and unique musical creation. There is no perfect English word to describe what is happening in this process. Blending. Merging. Melding. All of these point to mixing differing musical styles or genres of varied origins together into new artistic creations. Elsen Portugal prefers the term “fusion” over “hybrid”45—something more akin to a thick creamy soup than a mixed salad. Uday Balasundaram refers to “indigenous cosmopolitan music” for what is emerging in many urban church contexts.46

Whatever words one uses to describe this process, Christian artists, music bands, and worship teams are increasingly experimenting with artistic compositions developed from an amalgamation of features and styles with origins in previously established genres. One well-known example of how this happens is the emergence of jazz from ragtime, folk music, spirituals, work songs, blues, and various West African cultural and musical expressions.

Exportation—where indigenous song tunes, texts, and rhythms are exported from Majority World churches and incorporated into the worship services of churches in the West or elsewhere in the global family. In ٢٠٠٣, the international assembly of Mennonite World Conference took place in Bulawayo, Zimbabwe. At that gathering, the worship team taught a song in the Shona language—“Hakuna wakaita sa Jesu” (“There’s No One Like Jesus”)—to conference participants. It became a favored selection at the conference and eventually a kind of theme-song for the worshippers gathered from dozens of countries around the world. Six years later, this song followed conference participants to the ٢٠٠٩ MWC gathering in Asunción, Paraguay, and after that assembly, the song traveled to the 2015 conference in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Many participants at these gatherings carried “Hakuna wakaita” with them back home and taught the song to worshipping fellowships in their local communities.47 As cultural interactions increase through travel, social media, and digital resources, artistic expressions of all kinds will most certainly be migrating in multiple directions and finding new homes in faith communities far beyond their contexts of origin.

Internationalization—where tunes, texts, and rhythms from the global faith family beyond the West or other imported sources and one’s own local context become incorporated into the life, worship, and witness of the church. This stage is a logical outworking of afore-mentioned intercultural encounters and dynamics. In contrast to “contextual” music—referenced above in the 1996 Nairobi Statement on Worship and Culture—this music is of the “cross-cultural” variety.14 On any given Sunday morning in Abidjan, Ivory Coast, at the Cocody Baptist Church, one can experience music selections from Nigeria, Martinique, the Congo, and South Africa, along with praise and worship contributions from Switzerland, African American sources, Israeli folk tunes, and revivalist-style choruses from the early twentieth-century inherited French hymnbook, Sur les ailes de la foi.48

This international worship diet will most certainly be “the” encounter of the twenty-first century, vastly broader and richer than the bilateral relationships that have characterized so much of the colonial experience between Western and Majority World churches up until now. Already present and practiced in many urban, multicultural, and immigrant-shaped congregations, this music moves us ever closer to the biblical vision captured by the evangelist John in Revelation 7:9–10, where all history is headed.49

Three MWC Member Churches Reflect on Music in Worship

It would be fascinating to begin documenting all of the many and diverse patterns of missional worship taking place in Anabaptist communities in almost one hundred countries worldwide. As a timid beginning to a much more comprehensive research project still waiting to happen, we asked representatives from three MWC member churches to reflect on music in the lives of their worshipping communities. Here is a brief summary of those reflections:

Ethiopia50

During the time of the early missionary influence in the 1950s, the Ethiopian church sang mostly Western songs translated into the Amharic language. These were often awkwardly sung and disappointing to some of the foreigners who were familiar with the songs in their original contexts.

Then, in the 1960s, with the Semaye Birhan revival, young people began composing their own songs with traditional, culturally appropriate tunes. Western songs disappeared, and the new songs took center stage.

Today, the church sings their own indigenous songs in local languages, with tunes in the pentatonic scale but accompanied by Western musical instruments. Only a few indigenous instruments—such as the begena (harp), washint (flute), and kebero (drum)—are in use. This is a problem for the church’s mission, since, as a result, many local onlookers view the church as a Western religion.

Indonesia51

Dutch Mennonite missionaries arrived in Indonesia in the mid-nineteenth century, bringing with them their European worship practices. Kidung Pasamuwan—a collection of Western hymns translated into Javanese—was published in 1887 and is still in use today. Keyboard accompaniment is the general rule for these songs, though youth prefer drums and guitar.

Over the years, three branches of the Mennonite church have emerged in Indonesia: (1) the “Javanese Evangelical Church” (GITJ), with hymns sung mostly in Javanese, occasionally in Indonesian, and accompanied for special occasions by indigenous instruments; (2) the “Muria Christian Church of Indonesia” (GKMI), rooted since the 1930s in the resident Chinese population, employing primarily translated Western hymns in Indonesian, though original compositions are emerging; and (3) the “Christian Congregation in Indonesia” (JKI), a 1970s charismatic offshoot of GKMI. This group, youthful and urban, sings contemporary praise and worship music styles in Indonesian and English and makes use of both imported global selections and their own indigenously composed contemporary styles.

One Jakarta-based JKI congregation has exported via social media its own original compositions to churches across Indonesia, to Japan and Thailand, and beyond. In Indonesia—the world’s most populous Muslim country—the worship practices of the church often communicate that Christianity is an imported religion.

Zimbabwe52

The first Brethren in Christ (BIC) missionaries arrived in Zimbabwe in the late 1890s. Rather than translating Western hymns into the local siIndebele language, they made use of and adapted an existing Zulu-language collection of European hymns, Amagama Okuhlabelela, produced in South Africa.53

Dr. Barbra Nkala recast the classic hymnbook into colloquial siIndebele, incorporating additional music pieces from other church traditions. The project never blossomed, however, because of a general preference for the classic hymnbook, and widespread financial challenges that hindered BIC congregants from purchasing a new hymnal.

Indigenous drums and singing with dance have generally been forbidden or discouraged over the years for fear of syncretistic influences. The country’s ever-deepening cycles of economic indebtedness and the church’s patriarchal leadership have done little to encourage indigenous creativity, though choral competitions and special music groups occasionally produce and perform new compositions.

Most importantly, South Africa’s powerful presence on the southern border has continually shaped music in Zimbabwe through its spiritually inspired resistance anthems to Apartheid and the constant flow of worship songs and recordings that Zimbabwean youth find more attractive than focusing on music of their own creation. Young Zimbabweans currently are producing very little worship music, and their music is not being assimilated into the mainstream worship of BIC churches. The spark, however, for potential hymnodic shift is there!

“Remembering Forward:” A Few Concluding Thoughts

Sixteenth-century Anabaptist leaders could never have imagined that in five hundred years the “Western” branch of the Anabaptist faith story would be in the minority alongside burgeoning—and sometimes persecuted—faith communities in African and Asian contexts in what is becoming a truly global conversation. As we all prayerfully discern and attempt to faithfully live out our commitment to the gospel and the Anabaptist stream of faith, we have so much to learn from one another about what worship could, should, and will look like for missional faith communities with Anabaptist commitments.54 Our reflections in this essay will hopefully contribute to an exciting new chapter of research and discovery opening up before us. Que la rencontre commence! May that encounter begin!

Janie Blough served in ministry in Paris, France, for forty-five years under the auspices of Mennonite Board of Missions and its successor organization, Mennonite Mission Network. She completed a Doctorate in Worship Studies at the Robert E. Webber Institute for Worship Studies (Jacksonville, Florida) in 2014. She has authored various writings related to worship and worship praxis—the vast majority in French—including Dieu au centre! (Éditions Mennonites, 2014). She continues to write; lead worship at the Châtenay Mennonite congregation (Châtenay-Malabry, France); and teach in theological schools, continuing theological education programs, and congregations throughout France, Switzerland, and beyond.

James R. Krabill served for forty-two years with Mennonite Board of Missions and its successor agency, Mennonite Mission Network, as a Bible and church history teacher among African-initiated churches in West Africa and an administrator for mission communications and global ministries. He completed a doctoral dissertation on African hymnody at the University of Birmingham, U.K. (1989) and has since authored and edited various works, including Music in the Life of the African Church (Baylor, 2008) and Worship and Mission for the Global Church (William Carey, 2013). He currently serves as Senior Editor for the journal Global Forum on Arts and Christian Faith, and as Core Adjunct Faculty at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Elkhart, Indiana.

Footnotes

Alan Kreider and Eleanor Kreider, Worship and Mission after Christendom (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 2011), 23.

Thomas H. Schattauer develops this view in “Liturgical Assembly as Locus of Mission,” in Inside Out: Worship in the Age of Mission (Minneapolis: Fortress, 1999), 1–22.

John Driver, Life Together in the Spirit: A Radical Spirituality for the 21st Century (Walden, NY: Plough, 2015), 30. Kreider and Kreider hold the same view in Worship and Mission, 53–55.

Wilbert R. Shenk, “Why Missional and Mennonite Should Make Perfect Sense,” in Fully Engaged: Missional Church in an Anabaptist Voice, eds. Stanley W. Green and James R. Krabill (Harrisonburg, VA: Herald, 2015), 20.

Wilbert R. Shenk, “Jesus and Mission,” in Jesus Matters: Good News for the 21st Century, eds. James R. Krabill and David W. Shenk (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 2009), 195.

A portion of this article is adapted from an earlier, shorter essay by the same authors and published as “Worship and Mission,” in God’s People in Mission: An Anabaptist Perspective, eds. Stanley W. Green and Rafael Zaracho (Bogota, Colombia: Mennonite World Conference, 2018), 113–25.

John Driver, Life Together, 37.

This playful formulation is actually the title of Ruth A. Meyers’s book Missional Worship, Worshipful Mission (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 2014).

For more on the Anabaptists and Jesus’s final commission to the disciples, see the lecture by Malcolm Yarnell, “The Anabaptists and the Great Commission” at Southeastern Seminary (October 2, 2018), accessed February 7, 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7uEXnA1bOe0.

This view was shaped by two factors: (1) a kind of biblical literalism held by many Anabaptists and (2) Zwingli’s reaction to and rejection of medieval singing only by clergy and in Latin.

Paul Wohlgemuth, “Anabaptist Hymn,” Direction 1, no. 3 (July 1972): 92.

C. Arnold Snyder, Anabaptist History and Theology (Kitchener, ON: Pandora, 1995), 268.

See Beverly Durance, “The Unifying Power of Song: The Swiss Anabaptist Ausbund as a Voice of Convergence in a Divergent Movement” (master’s thesis, University of Calgary, 2007), 43–49. Another important resource describing the songs inspired by the early martyrdom period is Gerald J. Mast’s article “Suffering Mission in the Passau Songs of the Ausbund,” Anabaptist Witness 4, no. 2 (October 2017): 15–35.

Citing John Howard Yoder in Alvin J. Beachy, “The Theology and Practice of Anabaptist Worship,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 40 (July 1966): 166.

Paul M. Miller, “Worship among the Early Anabaptists,” Mennonite Quarterly Review 30 (1956): 245.

Edward L. Poling, “Worship Life in Sixteenth-Century Anabaptism,” Brethren Life and Thought 37 (Spring 1992): 122.

This concept is more fully developed by Wolfgang Schäufele, “The Missionary Vision and Activity of the Anabaptist Laity,” in Anabaptism and Mission, ed. Wilbert R. Shenk (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 1984), 70–87.

Harold S. Bender, “Hymnody of the Anabaptists,” in Mennonite Encyclopedia 2 (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 1955–59): 870.

Wohlgemuth, “Anabaptist Hymn,” 93–96.

Rosella Reimer Duerksen, “Anabaptist Hymnody of the Sixteenth Century” (PhD diss, Union Theological Seminary, New York City, 1956), 12–13.

Christian Neff, Mennonitisches Lexikon (Frankfort and Weierhof: Hege; and Karlsruhe: Schneider, 1913–1967), 2:86.

Hans Kasdorf, “The Anabaptist Approach to Mission,” in Anabaptism and Mission,” ed. Wilbert R. Shenk (Scottdale, PA: Herald, 1984), 63.

Beginning in 1925 and for the next fifty years, these gatherings took place in either Europe or North America. In the past five decades, international settings have been chosen where large Anabaptist populations are located— Brazil, Zimbabwe, India, Paraguay, and Indonesia.

Bergen’s original three-stanza hymn has a fourth verse (stanza 2) added in hymn no. 797 in the newly released North American Mennonite hymnal Voices Together

(Harrisonburg, VA: MennoMedia, 2020).

As of 2018, MWC membership included 1 international association and 107 Mennonite and Brethren in Christ national churches from 58 countries, with baptized believers in about 10,000 congregations. Over 80 percent of these believers are African, Asian, or Latin American, with less than 20 percent located in Europe and North America. See “Mennonite World Conference” website, accessed February 8, 2021, https://mwc-cmm.org/about-mwc.

Additional reflections on the content of this hymn and a deeper analysis of major themes in Anabaptist missiology can be found in my chapter, James R. Krabill, “Characteristics of Anabaptist Mission in the Sixteenth Century,” in Sixteenth-Century Mission: Explorations in Protestant and Roman Catholic Theology and Practice, eds. Robert L. Gallagher and Edward L. Smither (Bellingham, WA: Lexham, 2021), 188–207.

Bender, “Hymnody of the Anabaptists,” 870. The author to whom Bender refers—Rochus Wilhelm Traugott Heinrich Ferdinand Freiherr von Liliencron—was a Germanist and historian, known in particular for his collection of German Volkslieder (folk songs) published in five volumes over a four-year period from 1865 to 1869.

See Rom 5:10–11; 2 Cor 5:18–19; Eph 2:14–16; and Col 1:19–22.

N. T. Wright, “Mere Mission,” Christianity Today interview, January 2007, 41.

For more here, see J. G. Davies, Worship and Mission (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1966), 36.

This expression, missio Dei, is a Latin term meaning “the mission of God” or “the sending of God.” For the quote, see Kreider and Kreider, Worship and Mission, 255.

Mark Labberton, The Dangerous Act of Worship (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2007), 14.

The full text of the 1996 document by the department for Theology and Studies of the Lutheran World Federation is available at https://worship.calvin.edu/resources/resource-library/nairobi-statement-on-worship-and-culture-full-text (accessed February 8, 2021).

Wilbert R. Shenk, “An Anabaptist View of Mission,” in Anabaptism and Mission, eds. Wilbert R. Shenk and Peter P. Penner (Schwarzenfeld, Germany: Neufeld Verlag, 2007), 58.

These observations and the accompanying chart are adapted from the work of Ron Man in his chapter, “‘The Bridge’: Worship between Bible and Culture,” in Worship and Mission for the Global Church: An Ethnodoxology Handbook, ed. James R. Krabill, with Frank Fortunato, Robin Harris, and Brian Schrag (Pasadena, CA: William Carey Library, 2013), 17–25.

See Charles and Rah, Unsettling Truths: The Ongoing Dehumanizing Legacy of the Doctrine of Discovery (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity, 2019), 86.

J. H. Nketia, “The Contribution of African Culture to Christian Worship,” International Review of Missions 47 (1958): 274

See W. J. Wallace, “Hymns in Ethiopia,” in Practical Anthropology 9 (November–December 1962): 271.

See Mary Key, “Hymn Writing with Indigenous Tunes,” Practical Anthropology 9 (November–December 1962): 258–59. The lively debate among Roman Catholics about the adaptation of the liturgy to new contexts of ministry would also provide examples of this process.

Charlina Gozali was a master’s level student in a 2011 class that I (James Krabill) taught on “Theology of Song” at Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California.

Asante Darkwa, “New Horizons in Music and Worship in Ghana,” African Urban Studies 8 (Fall 1980): 69.

Ephraim Amu, Amu Choral Works, vol. 1 (Accra: Waterville, 1993).

E. Bolaji Idowu, Towards an Indigenous Church (London: Oxford University Press, 1965), 30–31.

Vida Chenoweth and Darlene Bee, “On Ethnic Music,” Practical Anthropology 15 (September–October 1968): 212. One of the most remarkable examples of this approach applied in mission is the posture taken by the Liberian evangelist William Wade Harris during his phenomenally successful West African ministry (1913–1915) described in two publications by James R. Krabill: The Hymnody of the Dida Harrist Church, 1913–1949 (Frankfurt/M.: Peter Lang GmbH, 1995), and “Gospel Meets Culture: A West African Evangelist Provides Clues for How It’s Done,” in Is It Insensitive to Share Your Faith? Hard Questions about Christian Mission in a Plural World (Intercourse, PA: Good Books, 2005), 88–102.

See Portugal’s doctoral dissertation, “Fusion Music Genres in Brazilian Indigenous Churches: An Evaluation of Authenticity in Xerente Christian Contexts” (Irving, TX: B. H. Carroll Theological Institute, 2020), esp. 16–19.

See Uday Balasundaram, Creativity and Captivity: Exploring the Process of Musical Creativity amongst Indigenous Cosmopolitan Musicians (ICMs) for Mission, American Society of Missiology Monograph Series 51 (Eugene, OR: Pickwick, 2021).

Hakuna wakaita” is now in Voices Together, the denominational hymnal for Mennonite Church USA and Mennonite Church Canada.

Sur les ailes de la foi, chants anciens et nouveaux (Paris: Hachette, 1928).

Yet another category should be referenced here—one we might simply call “Revelation.” In some instances, churches consider their music to be of divine origin rather than a result of cultural encounter. For some members of Africa’s largest independent church—the Congo’s “Church of Jesus Christ on Earth through the Prophet Simon Kimbangu”—the movement’s hymns are seen as not humanly composed by those with musical gifts but rather “captured” (captés, in French), received by revelation, under inspiration or “coming from above.” See Gordon Molyneux, “The Place and Function of Hymns in the EJCSK,” Journal of Religion in Africa 20, no. 2 (June 1990): 153ff.; Wilfred Heintze-Flad, L’Eglise kimbanguiste: Une église qui chante et prie (Leiden: Interuniversitair Instituut voor Missiologie en Oecumenica, 1978); and Aurélien Mokoko Campiot, Kimbanguism: An African Understanding of the Bible (University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania University Press, 2017), 221–27. One finds a variation of this view in the Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahïdo Church. Here, some historians ascribe to a supernatural revelation of sixth-century patron Saint Yared—composer and pioneer of Ethiopian religious music—in which he was transported to the garden of Eden in heaven by three angels disguised as white birds, to learn the plainsong of Paradise; see Ephraim Isaac, “Ethiopian Church Music,” in The Ethiopian Orthodox Täwahïdo Church (London: The Red Sea Press, 2013), 103–7

Nine church leaders of Ethiopia’s Meserete Kristos Church (“Christ is the Foundation Church”) shared reflections with us August–October 2020: Tariku Wondimu, Getachew Tegegne, Ahmed Ahmed, Frew Tuke, Girma Bossen, Sisay Worku, Desta Debele, Teferi Setena, and Henok Mekonin.

Our informant here, interviewed on October 30, 2020, was Andios Santoso—church leader in the Gereja Kristen Maranatha Indonesia (GKMI) and currently a student at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Elkhart, Indiana.

Sibonokuhle Ncube, a member of Zimbabwe’s Brethren in Christ church, is currently studying at Anabaptist Mennonite Biblical Seminary, Elkhart, Indiana. On October 30, 2020, she graciously shared with us these reflections.

Amagama Okuhlabelela: Zulu Hymnal was published in 1911 for the Zulu Mission in Natal, South Africa, by the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, Boston, Massachusetts. It is still in print and available from The Mission Press, P.O. Box 37088, 4067, Republic of South Africa.

A good start for this awareness is the MWC website, under “Publications and Resources” (https://mwc-cmm.org/publications-resources), which posts a wealth of multi-language material on global worship, study tools, and intercultural encounters. See, for example, Transmission 2020, the French Mennonite video and study guide on Mennonite church life and worship in Ethiopia, https://mwc-cmm.org/resources/transmission-2020-ethiopia, accessed February 8, 2021. (Video is 10:14 in length.)